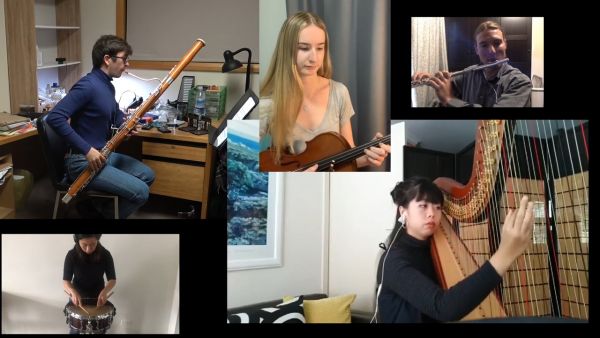

104 Concert Halls: Ravel's Boléro (from home) by the University of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Most arts and music disciplines rely on collaboration, but maybe none more so than orchestral performance. By its nature, an orchestra is a collective – the trick, more than performing as an individual, more even than being an attentive member of the constituent string, wind, percussion, or brass families, is to elevate the whole to much more than a sum of its parts.

And so, having 104 Melbourne Conservatorium student musicians perform and record Maurice Ravel’s 1928 masterpiece Boléro from their homes in the age of COVID-19 social distancing was always going to present a challenge. And yet that’s exactly what University of Melbourne conductor Richard Davis, Associate Professor at the Melbourne Conservatorium, chose to do.

“Concerts form part of our ongoing orchestra assessment,” says Davis, “so I had to think of a way to satisfy that policy and still deliver an ensemble project … in isolation.”

In April, he sent each member of the University of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra detailed information on what he expected of them, in a document titled Program Boléro (Covid-19 Arrangement). Rather than playing together, they would be recording their individual parts on smartphones and computers to a rhythm track recorded by a student percussionist under Davis’s direction immediately pre-lockdown. While the scale of the project was huge, the decision to record the 17-minute Boléro was, in Davis’s words, the “obvious choice” given its “unwavering and relentless and metronomic” nature.

104 Melbourne Conservatorium musicians perform Boléro from home with musical direction by Associate Professor Richard Davis.

“The piece repeats itself many times – passing the famous theme from one instrument to another, from one section to another, gradually building and growing,” he says. “However, what is not known, even by many players, is that each time the theme comes, it is very slightly different – it mutates as it infiltrates the orchestra. Each change is almost imperceptible, but they are definitely there. I liken it to the children’s picture game where two pictures seem the same but, when you look closely, there’s a difference. I asked the players to exaggerate those differences as they are so often ignored by players and conductors.”

Using a standard metronome, he says, was a non-starter, as the speeds between one metronome and another can vary, albeit slightly. “Just get two quartz clocks and align the second hands and within a few hours they’ll be out,” he explains.

“I thought a better and more meaningful ensemble experience was to get the iconic side drum recorded with me present. We did this in March, on the last day we were allowed into the Conservatorium building. And that side drum track was then sent out to all the players with strict instructions about how to record, how to phrase, and so on.”

“Everything relied on us getting the side drum part in the can because, without it, there would be no Boléro project.”

That particular responsibility fell on percussionist Yiang Shan Sng, a University of Melbourne student and graduate of Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) in Singapore who has been performing with the University of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra since March last year.

“I've done a few tape auditions over the past few years,” Yiang Shan says “It felt lonely playing the side drum part without the orchestra. I remember it was a very stressful day as the percussion department was busy trying to get instruments shipped to all the students' homes so that they could continue with their studies away from campus.

“I realised about a quarter of the way through the piece that my breathing was very shallow, and I had to take a break to deal with that. But it was a very enjoyable experience overall to be part of something so meaningful during this pandemic.”

While unexpected, the experience, she says, has been valuable. “The attention to detail and the ability to switch to a different mode as compared to being on stage has taught me a lot and has opened up many new possibilities for collaborating with artists from elsewhere.”

“I hope our virtual performance of Boléro can give everyone some comfort and strength in these difficult times and show our collective appreciation to all the essential workers all around the world.”

Almost miraculously, she says the final recording sounds “as if we were in the concert hall together performing this piece”.

Davis purposely chose Ravel’s preferred speed for Boléro – one that was famously ignored by Toscanini and caused a great argument between the conductor and composer “I thought Toscanini’s speed of 72 beats per minute was too trivial and light-hearted to play during this pandemic whilst the original tempo seemed more representative of social isolation,” he says. “The slower tempo requires more patience, adds a greater tension and is therefore more euphoric and powerful when it finishes.”

Director of the Melbourne Conservatorium Professor Richard Kurth says Ravel’s 1928 Boléro is especially resonant for a project of this type in this historical moment. “The ostinato rhythm and the repeated melodic theme constitute a regimented frame, much like the restrictions we all are experiencing,” he says. “But they also provide a wonderful opportunity for showcasing all kinds of individual differences, from striking contrasts to subtle nuances. This project really celebrates the personality of each player.

“There is also the unsettling military effect of that persistent side drum rhythm and the gradual overwhelming build-up and climax. There is an ominous element, as though Ravel was reflecting on the Great War just past, or anticipating the political and military events that would unfold in Spain and Europe just a few years later. In these ways, and many others, this music and this project help us reflect on individual experience and larger social phenomena.

“It reminds us that all music becomes deeply infused with contemporary and historical meanings, and speaks to our intellect and psyche in many ways. And it offers catharsis. In witnessing this project, we derive strength from its celebration of our individualities and our collaboration as a community."

Earlier this month, Melbourne Conservatorium of Music students presented a heart-felt rendition of Tchaikovsky, Symphony No.5 from home to say thanks to their Orchestra mentors and staff.

Working with long-term sound-recording colleague Haig Burnell, who he describes as a “recording and ‘tonmeister’ genius”, Davis planned the project in incredible detail, with Davis describing his role in sporting, rather than conducting, terms.

“I have trained these wonderful musicians and I trust them implicitly,” he says. “My work was all in the preparation for this project – not to mention all the work we’ve done together in recent years – just as a football manager works behind the scenes before a match.”

Davis, who played as principal flute with the BBC Philharmonic for more than 30 years, said he faced doubts from former colleagues when he told them he planned to record the piece using multitracking – layering individually recorded tracks to complete the whole – rather than the standard process for classical music, in which the music is balanced in the room and played live. “I was told that having more than nine instruments would present a very difficult challenge to make it sound like an orchestra,” he says. “Haig has managed to join together 104 musicians, and the musicians sound incredible.”

One of those musicians, Ha Jeong Choi, a flautist, who is completing her Honours year in the Bachelor of Music at the Conservatorium, describes the project as an “eye-opening” experience.

“Because the flute is the first melodic instrument to be heard, I wanted to play it as best as I could,” she says. “I still think my final recording could have been better in many ways, but I had a lot of fun playing such a well-known piece.”

“One challenge was staying focused during the recording process, which often became repetitive. After listening to the piece and the solo countless times, I noticed that my perception of the music became somewhat numb. I sent short recordings to friends who play different instruments, which helped me refresh my ideas on rhythm, colours, use of vibrato, and more.

“It also took me a while to find a good visual set-up and acoustic for the recording. With limited equipment, I had to stack a bunch of books together to put my phone on, and had to play in a space that was not carpeted. I even considered playing in the bathroom because of the resonant acoustics.

“I then realised that some of the takes I was initially happy with caught unwanted noises, so I had to re-do those. It took me days to get to the final recording but I found it enjoyable, because it was a new experience.”

Clearly, the experience was different in almost every way to playing in a live orchestra setting, but – given necessity is the mother of invention – it has also opened up new possibilities.

“Participating in this project has made me realise how playing with others can create a special ambiance and energy,” she says. “Now that ensemble-playing is not allowed, I am starting to think that I may have taken it for granted before. I think I’ll have a very different approach to ensemble-playing once we are all able to play together again. I will definitely appreciate it more.”