Professor Barry Conyngham – reflections of the outgoing Dean of Faculty of Fine Arts and Music

When Barry Conyngham finishes up as Dean at the end of 2020, he will leave behind a faculty transformed in everything from its name to its trajectory. Here, in an edited interview with Paul Dalgarno, he discusses what was, what is, and what will be at the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music.

When I accepted the position of Dean of what is now the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music in 2010, I had no idea I’d be in the role for a decade.

I was already beyond my mid-sixties and had been out of full-time academia for about 10 years. Previously, I had been Dean of Creative Arts at the University of Wollongong (1989–1993) and Foundation Vice-Chancellor at Southern Cross University (1994–2000), after which I accepted the Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University.

On returning to Australia in mid-2001, my wife Deborah and I built our dream house in the hills between Byron and Lismore, where I spent much of my time writing music and enjoying a relaxed life of music, travel and the occasional university consultancy.

Attempts had been ongoing from about 2007 to 2010 to create a single faculty from the Victorian College of the Arts and the Melbourne Conservatorium but, for a number of reasons, it hadn’t really worked. Because of the building effort I’d made at Southern Cross, and consultancy work with universities thereafter, I had a reputation for being able to deal with issues and move things forward.

And because I had worked at the Melbourne Conservatorium for 14 years and had many close colleagues and friends at the VCA, I was, I think, seen as the right person to deal with a challenging situation. Indeed, I thought, "Well, I could at least give it a go, get a few things done in two or three years." As it turned out, it just kept rolling out from there for the rest of the decade.

The first thing I had to deliver on was the commitment by the State and Federal Governments to assist in the Faculty’s financial problems, and to give some kind of timeframe for mending and repositioning two fantastic institutions – the 120-year-old Conservatorium and the nearly 40-year-old Victorian College of the Arts.

My experience as a vice-chancellor helped, but, as a composer, I was also an established artist who could look the staff and students in the eye and say, "I know how it feels, I know how frustrating it is, I know you need more resources, I know you need to hold on to your to studios, to one-on-one teaching," and I was committed to those things from day one. However, what I had to deliver in the first year was a financial base from which we could have a plan to rebuild.

In 2011, we secured Federal and State capital and additional operating financial support to begin the journey.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

When I began at the Faculty, it was known as the Faculty of VCA and Music, a simple joining of the names of the two previous faculties, but for me it was an annoying category mistake because it paired an institution and a discipline. So, within the first year I put forward the idea that the name should signal the two institutions to become the Faculty of the Victorian College of the Arts and the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music, which, apart from being the world's longest title, at least said who we were.

But it soon became the VCA & MCM, which to me was far from perfect: the first part (VCA) came with a history of identification, but the second (MCM) was not so clear, and indeed obscured the traditional name of the Conservatorium.

Also, it did not look like the name of a faculty in a university, nor reflect the completeness of all the artistic disciplines. After a lot of canvassing of names, I realised it was hard to argue against the idea of combining the names of the two undergraduate degrees, the long-established Bachelor of Music and recently created Bachelor of Fine Arts, so in 2018 we became the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music.

This allowed the preservation of the two institutions inside a faculty with discipline-based names. It also brought us more in line with the other academic units in the University – something I’m always keen to emphasise given the University of Melbourne is the number-one university in the country and an organisation that changes the world.

PRECINCT

But the joining of the Conservatorium and VCA into one Faculty had to happen in more ways than just the name. Improving and expanding upon our standing in what has since become known as the Arts Precinct was another major aim.

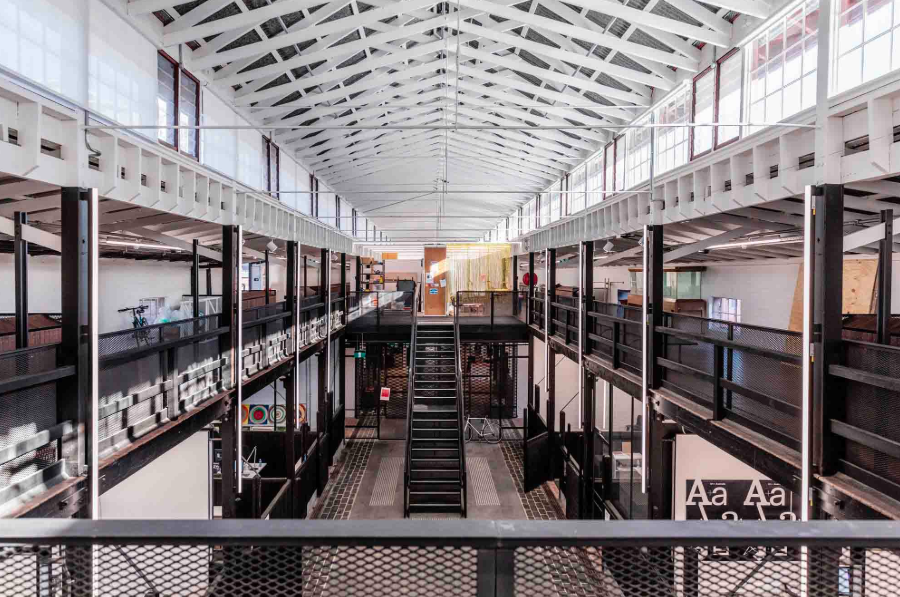

The VCA campus was situated right in the heart of the Melbourne Arts Precinct, with more than 20 other major arts organisations close by. It was a powerful aspiration to move most of the Conservatorium to Southbank. The old Conservatorium building, Melba Hall, had been built in 1912 for about 80 people, but by 2011 we were heading towards more than 800 students and staff scattered around in buildings all over the University’s Parkville Campus. If we could move the majority of the Conservatorium students to Southbank, we could create a truly world-class campus that was still very much connected with Parkville, but with all of the arts disciplines in one place, for the first time ever.

The Ian Potter Southbank Centre, opened in 2019, is the jewel in the crown of the $200 million Southbank campus redevelopment.

The first challenge was to have all of the Southbank area devoted to the arts and enough room to accommodate a new specialised music building. To achieve this, we had to secure the remaining buildings from what had been a huge police complex from the early 1900s.

And so, acquisition of the final set of buildings, the Victoria Mounted Police stables, became the first mission. If they were developed as visual art studios and a performing arts space, the entire area would be available for practical arts education and performance.

Working with the Government, the University and our great philanthropists and supporters such as Martyn Myer was essential to realising the dream. Martyn is a big-picture person, who comes from a family with a tradition of having big ideas, and big ideas focus people's attention. If people know there's a good view at the top, they don't mind how hard it is to climb the mountain.

It took a few years, and thousands of conversations, to achieve this first step, to get agreement that the mounted police would move to new facilities, but in 2014 the heritage-protected buildings became ours and the award-winning facility we now have – The Stables and the Martyn Myer Arena – opened in 2018. Incredibly, as this fell into place, the State, the University and philanthropists accepted a vision that was to affect the whole campus.

This momentum included, at its centre, the creation of a new Conservatorium building. The Ian Potter Southbank Centre opened on the campus in 2019, and is very much the crowning glory of what evolved into a $200 million cascade of renovation and capital works that have transformed our facilities over the decade.

THE WILIN CENTRE

I’m also very proud of the Wilin Centre for Arts and Cultural Development at the Faculty, which exists to provide pathways for Indigenous students into the arts, and into the University of Melbourne. Although the Centre is currently thriving in terms of research, personnel and advocacy, and has certainly expanded during my time at the Faculty – as has the aim of embedding Indigenous expertise and knowledge across all disciplines – I think it’s also fair to say that we still haven't got anywhere near far enough.

Indigenous culture, and the way it’s overlooked, remains a big problem in Australia, and any form of prejudice or practice that leads to inequity is just unacceptable. I hope to see work at the Wilin, and at the Faculty, reflect this belief – and continue to improve on this situation – in the years ahead.

Because of all the building and renovation work that’s happened on campus in recent years, I’ve been told I have an “edifice complex”, and I think that’s true. But to transform and add to the physical nature of the Faculty is not enough. It’s about so much more than just bricks and mortar, glass and steel.

The big question was, and is: "What are you going to do with all these new buildings?" The only reason people give you resources to build beautiful spaces is because of what you're going to do in them – build the capability, the expertise and the passion of the staff and ultimately deliver for the most important aspect of the Faculty, our students.

STUDENTS

I’ve always gone to every show, exhibition and performance I can go to by our students – and why wouldn’t I? I like seeing wonderful people at the peak of their art doing their thing. Seeing our students going from where they are when they first walk in to where they are three or four years later is really great. I'm very fond of saying, "I'm the only person who really can do this, go to all of the shows, exhibitions and presentations”, and that’s been a fabulous part of my job, seeing what our students and staff can achieve.

Students being able to practise and improve their art, craft and research in the company of other like-minded people is such a valuable opportunity. I always say to the students during orientation week, "You could be sitting next to the person you're going to spend the rest of your life with” because, particularly between the ages of 18 and 24, a lot of stuff happens; and for an artist that’s even more heightened because art is about absorbing experience.

I think it’s really important to give young people a chance to figure out how to interact with others and explore creativity, and in our Faculty I find it interesting that even our professional staff, the non-teaching staff, are often themselves artists or serious consumers of art. I think that's one of the things that makes our Faculty really special.

In a more hard-edged reality, the university system is predicated on critical mass. You have to have a concentration of just enough students to afford the appropriate range of staff. And in our case, with specialised atelier-style teaching and relatively small cohorts of roughly 20 to 30 students per discipline, that’s been another issue to address during my time at the Faculty.

Over the 10 years of my tenure, we’ve increased the number of students studying our degrees, undergrad through to PhD, from about 1600 to about 2400, or roughly 50% – that's not a huge increase over 10 years, but it's enough for critical mass.

But there was also another opportunity. One of the elements of the University's undergraduate program is to encourage students from one faculty to take a single subject in another: the so-called breadth model. The expansion of our breadth subject offerings has meant that our subjects are now taught to roughly 12,000 students from other parts of the University every year.

And, as we expanded the impact of our specialist artistic teachers, so we expanded our income. To put it simply, those extra resources have provided the capacity to hire more specialists who have more opportunities to teach across all of the subjects and disciplines we offer. By enabling some practical arts education to others, we are able to better give an intense and fulfilling experience to our own.

2020

This year, of course, COVID-19 has thrown much of what we’d been doing previously into the air. I’ve been amazed by the speed with which our staff and students have transitioned to online teaching and learning, and also by what has come out of this in terms of performances, exhibitions and new ways of connecting artists from all disciplines with one another. While being forcibly separated from one another, I feel there has also been a renewed sense of our shared purpose as a Faculty.

In April 2020, more than 100 Melbourne Conservatorium musicians performed and recorded Maurice Ravel’s 1928 masterpiece Boléro from their homes.

Despite all the difficulties, this year has become a special experience, and hopefully a unique one, as none of us would want to go through what we’ve been through this year too often. We now have to figure out what we take away from the experience of 2020. As a society, not just as a Faculty, we won't go back to how things were in 2019, and we certainly don't want things to be as they’ve been in 2020. People talk about COVID-normal, and that will be a new state, which in time will also change, and I think, artistically, that’s really fascinating.

LEGACY

As the outgoing Dean, one of the things I’ll lose on 31 December will be responsibility. I like having responsibility, and will be sad to lose it, not least because I believe the first thing you do with responsibility is give it to other people, to enable them to work at their best.

I do acknowledge that I’ve achieved things during my time as Dean but I'm also realistic about what so many others have contributed. I use the words “luck” or “good fortune” quite a lot because it's simply too complicated for any one person to control what actually happens. You just do what you can and hope you make the right choices and encourage others to make the right choices too.

Pragmatism is about compromise. There are a whole lot of things I would have liked to have done, and if I’d been more authoritarian, I might have achieved them. But I don't think I would have enjoyed that because I genuinely like seeing people do their thing, just as I'm always more than happy to have the chance to do my thing. The joy for me comes from being able to say, not only did I have things happen that I thought were really useful and important, but that I was surrounded by people who also were part of that feeling and shared in that.

When I’m no longer Dean the responsibility, and everything that comes with it, will quickly disappear and, after a fallow period in composing music this year, I hope to return to composition. I’ll be more self-occupied, and I suspect life will be much more about me from now on. I’ll focus my energies on music. The artistic experience will be more personal. I won't necessarily be sharing other people's, young people’s, artistic journey so thoroughly.

But solitude to create can also be very good. Artists tend to like that.