An artist bears witness to those detained on Manus Island

Manus Island refugee processing may be coming to an end, but new portraits shine a light on the lives left in limbo.

In late October 2017, the Australian government announced the imminent closure of the Manus Island Regional Processing Centre in remote Papua New Guinea (PNG).

Since its opening in July 2013, more than 1,500 men, most of whom were found to be genuine refugees, were transferred there as part of the Australian government’s offshore processing strategy.

Many had languished in detention for three or four years before the centre was closed. Six years later, some of those men are still in PNG, waiting to be told of their future.

Like many Australians, I was shocked by these developments, particularly in the light of reports that the new facilities were inadequate and that there were ongoing safety concerns for the men.

I remember the riots, which led to the murder of Reza Barati in 2014, and had heard that tensions between PNG locals and asylum seekers had only worsened

I wondered whether I could use my small platform as an artist to do something. And the more I thought about it, the more I felt I had to.

So, I decided to travel to Manus.

During those few days when media attention turned towards the plight of these men, one voice in particular could be heard reporting tirelessly from the inside: that of the journalist and activist, and now acclaimed novelist, Behrouz Boochani.

I made contact with him and told him I was coming, in the next few weeks if possible. He wisely told me to wait, knowing that, as a photographer, it would not be easy for me. We would need a plan, he said.

So, over the next few months, we came up with one.

In March last year, I travelled to PNG, and finally made my way to Manus Island.

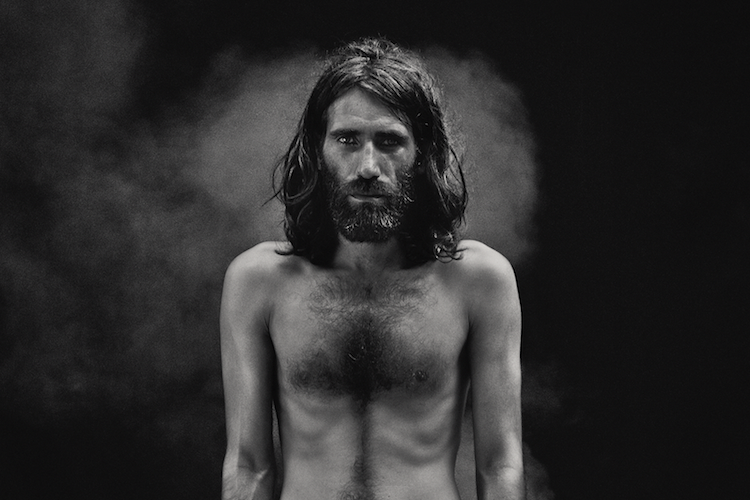

There, I spent a week with some of the most gentle, and fragile men I have ever met. Men who made the decision to flee war or other circumstances in their country, or to seek a better life, but who instead found themselves on Manus.

They have been stripped of those rights which, more and more, we regard as the privilege of citizens, and just because they were born into a world of unequal geographies.

I got to know Behrouz, and his circle of friends, too – a group of Kurdish men who share a language, and an experience of being stateless that binds them as a community. They have each other, at least.

I met other men, too; men who lacked even those fragile bonds. I would struggle to express in words just how broken they are.

Each day, they retreat further and further into a darkness which they lack the will, much less the words, to communicate.

In making Remain, the video work and image series that came out of that trip, my aim was not simply to tell their story. Nor was it to try to capture their humanity or their plight.

I had decided early on, that is, not to make a straightforward ‘documentary’ work, believing that the typical images of refugees only reinforces in the eyes of the viewer their inferior image and position.

It ends up justifying and, in a way, solidifying their destiny.

Instead, what we attempted to make was an artwork – using the language of poetry, performance, and song – that defies such logic, and forces the viewer to confront their own incomprehension, as well as the very inexplicableness of the situation that these men face.

But we also wanted to highlight something about our human situation which we all too readily forget.

We are not islands. We are social beings, and all of us depend for our well-being on the safety and bonds of a community.

But in the last decade, we have been made to think that men and women like those on Manus and Nauru represent a threat to the sanctity of our own community.

We have been told that, in order prevent the loss of lives, it is necessary to sacrifice a few; that we should be careful not to care too much.

We have watched politicians invent monsters for the sake of convincing us of the need for stronger borders.

But I was born in Iran at a time when a terrible war was being waged on the border with another nation, so I know what it feels like to live in fear because the enemy is waiting at the city gates; to be told to hide in the basement because the planes are overhead.

Here in Australia, we have been made to believe that the men and women we have placed in offshore prisons represent a coming threat like that. But they don’t.

This isn’t just about Australia. This is about a new world that we are seeing come into being before our eyes – a world in which the defence of borders depends on the drawing of new lines between the included and the excluded.

Between citizens and bare lives.

But these are very dangerous times, for what is being redrawn here are the limits of our human community. And the very fragility of those shifting lines means that, one day, any one of us might find ourselves on the outside.

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

Applications for the Graduate Certificate in Visual Art, at the Victorian College of the Arts, university of Melbourne, close on 31 October 2019. Visit Study for more details.

Hoda Afshar’s work features in the current issue of Art + Australia, Australia’s longest running art journal, published under various mastheads since 1916, and based at the University of Melbourne since 2016.