Music Therapy: from Melbourne to Würzburg

The University of Melbourne’s Music Therapy team has a strong connection with the German city of Würzburg – and it’s only going to get stronger.

By Paul Dalgarno

More than 90% of Würzburg in northern Bavaria was destroyed in 17 minutes by some 225 British Lancaster bombers in early 1945, producing a firestorm that killed 5,000 people. In lieu of any military targets, the World War Two raid was intended to break the population’s spirit. And yet, over the next 20 years, the buildings of historical importance were painstakingly reconstructed, mostly by hand, and mostly by the surviving female citizens, who became known as “rubble women”.

Today, the ancient Marienberg Fortress watches over the town and surrounding hills while the sun shines and people go happily about their business.

Among them is Professor Felicity Baker, who has been coming to Würzburg for nine consecutive years, and has come this time with her University of Melbourne Music Therapy colleagues – Dr Imogen Clark, Dr Jeanette Tamplin, and Dr Claire Lee – all of whom have travelled on a German-Australian Exchange Grant, and all of whom will present at a symposium focusing on music therapy and dementia care.

Among them is Professor Felicity Baker, who has been coming to Würzburg for nine consecutive years, and has come this time with her University of Melbourne Music Therapy colleagues – Dr Imogen Clark, Dr Jeanette Tamplin, and Dr Claire Lee – all of whom have travelled on a German-Australian Exchange Grant, and all of whom will present at a symposium focusing on music therapy and dementia care.

The minibus we’re in is laden with acoustic guitars. It’s being driven by Professor Thomas Wosch, a music therapist at the University of Applied Sciences Würzburg-Schweinfurt (FHWS) and Baker’s German counterpart on the Melbourne-Würzburg Dementia Songwriting Project.

Baker, who will present a keynote at the symposium, seems relaxed. “Yesterday was special because we went to Aloysius Alzheimer’s former house in Markbreit, which is about 30 kilometres from here,” she says. “And here we are, today, talking about music therapy and dementia.”

Wosch, who has been playing tour guide, slows the minibus to a halt, says, “And on your right, ladies and gentlemen, you can see we’ve arrived at the Faculty of Applied Social Sciences campus.”

The campus is in the hills, overlooking the city and seemingly endless trees: green on green on green.

We get out, carry the guitars, and begin setting up the lecture hall. Minutes later, people start arriving, and within no time the room has filled with music therapy students and colleagues from Germany, China, Russia, Slovenia, Poland, and elsewhere.

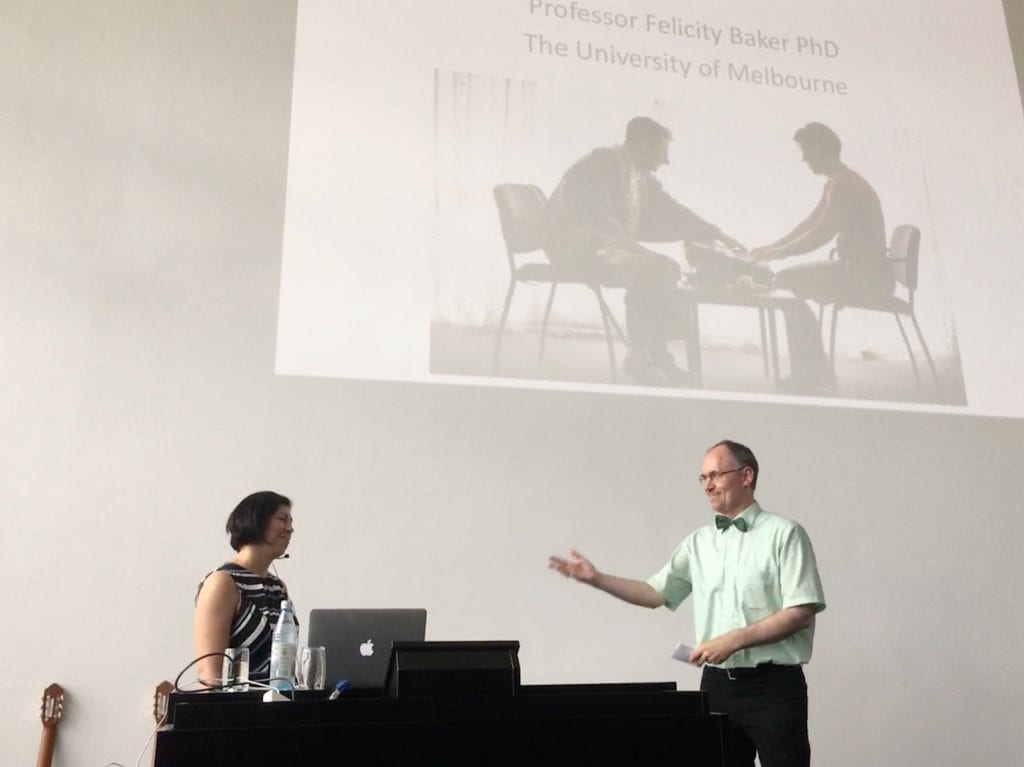

We get out, carry the guitars, and begin setting up the lecture hall. Minutes later, people start arriving, and within no time the room has filled with music therapy students and colleagues from Germany, China, Russia, Slovenia, Poland, and elsewhere.  Wosch, in a short-sleeved shirt and bow-tie, looks excited as he stands at the front of the room. He welcomes everyone from far and wide, giving a special nod to the Melbourne team, “because they’ve had to travel the longest distance to be here”.

Wosch, in a short-sleeved shirt and bow-tie, looks excited as he stands at the front of the room. He welcomes everyone from far and wide, giving a special nod to the Melbourne team, “because they’ve had to travel the longest distance to be here”.

“Many of you will know Professor Felicity Baker as she has a long history here and a long and distinguished career in Music Therapy,” he says.

“The Australian Government is very aware of the challenges facing many people and also of the potential for music therapy to provide non-medical treatments for people who are suffering or in need of relief.

“We’re very excited to have Felicity and her team here today, and look forward to more and more collaboration to build on our special relationship.”

Baker stands to applause, takes up position at the lectern, cues up her PowerPoint presentation. “As Thomas pointed out, we had to travel on a 24-hour flight to get here,” she says, to laughter.

“But, you know, in Australia we’re at the other end of the world, and if we don’t travel, we become very isolated. So when you ask, ‘Did you really come all this way for the symposium?’ – well, yes, we did.”

More laughter.

Baker glances at her first slide, looks at her audience, says, “I wanted to share with you how much is really going on at the University of Melbourne”.

“We’re very proud of our research profile – I would say we are the best in the world. The four of us who have come here today are currently involved in 11 funded projects. When I started at the University in 2013 we were five people, and now we’re 12.

“We have people working with adolescent and adult mental health, adult and child disability, in neuro-disability, autism, and dementia – both for people with dementia and their carers. We also have expertise in singing methods, songwriting, and improvisation. In other words, we pretty much do it all …”

The Melbourne-Würzburg-Dementia Songwriting Project started in 2016 and includes Baker, Tamplin, Lee and Clark, as well as Wosch and his two early-career researchers. Its research focuses on building and testing models of songwriting for people living with dementia and their family caregivers or formal caregivers, and builds on much of the international legwork done by Baker in recent years.

In the break after Baker’s presentation, I grab a moment with a woman who has been described by Wosch as the collaboration’s “first baby together”.

Jasmin Eickholt completed a Master in Music Therapy course at FHWS, where she still teaches, and is now enrolled as a PhD candidate in Music Therapy, researching dementia and late-life depression with Baker and her team at the University of Melbourne. She was in Melbourne in February, and will return in October, as she will continue to do twice a year for “intense workshops”.

“I really enjoy it,” she says. “Music therapy is very developed in Melbourne – they accept it more. I can apply what I learn there to my work here, because my research is based on German nursing home residents.”

She had originally thought about studying music for her undergraduate degree. “But I also like to help and support people,” she says, “so I decided to do social work instead. Mixing both of those things – the social work and the music therapy – has been very interesting.”

Dementia has been a key interest in Eickholt’s work to date, and she plans to combine this with research into the efficacy of positive psychology.

“Dementia is very serious, of course, and depression is often a comorbidity. In my experience of songwriting with people who have dementia, the music can really help them remember what they did, their pasts, a feeling of optimism, and so on – so that was my motivation to go into this area.”

Back at the lectern, at the start of the next session, Wosch is explaining his own circuitous route to music therapy.

“In between high school and university, I worked as a nurse assistant in a care home, where we had to wash and feed people,” he says. “I remember thinking: this is not enough, this can’t be everything we can do, we have to do something different.”

The “something different” for him was to bring his band to the nursing home during coffee afternoons. “We would play them folk songs,” he says. “It worked so perfectly, they really enjoyed it, and for me that was the first step.”

Practice and research not only on people with dementia, but their carers, is an ongoing focus at the University of Melbourne. Last year, Baker and her team secured substantial NHMRC funding for a world-first study into the use of music therapy for people with dementia.

“The people we’ll be working with will no longer be able to be look after themselves,” she said when the study was announced.

“They’ll be in aged-care homes 24-hours a day, either because they’re too unwell to stay home and look after themselves or their family carers are unable to look after them properly because the level of care they require is too great for the resources they have at hand.

“It’ll be one of the biggest music therapy studies in history – and certainly in dementia. It’ll be a game-changer, not just for us in Australia but globally.”

Dr Jeanette Tamplin’s work, meanwhile, on the Musical Memories “dementia choir” project, was last year expanded to include seven more choirs for people and carers living with dementia in Victoria and Tasmania. “We wanted to support carers in coping and adjusting in their role as well as people living with dementia,” she said at the time.

Supporting and feeding into both of those projects – as well as her own research – is Dr Imogen Clark, who now stands and approaches the lectern.

“We know that carers of people with dementia are at high risk,” she says. “They can become isolated, stressed, burnt-out or exhausted. They often have a poor quality of life, and we’re looking at ways to address that.”

In terms of research, it’s a knotty problem, with the global cost of dementia soaring to more than US$880 billion in 2015, but Clark’s work has taken on an unexpectedly personal dimension.

“My father was diagnosed with early-onset dementia about two years ago,” she tells the room. “But it really came to a head for my partner, daughters and me when my mother suddenly needed cardiac surgery and my father had to come and live with us. I thought: I can do this, I’m an academic and I’ve got a whole load of techniques to handle this. But, oh my goodness, I had no idea.”

The emotional rollercoaster since – negotiating a period of residential care for her father, dealing with the fallout of that decision – has been “horrendous”, she says. “I guess I’m telling you all this story because it shows how complex the situation is, and how important the situation is, not only for the primary caregiver but for all the family members of someone who is living with dementia.”

The emotional rollercoaster since – negotiating a period of residential care for her father, dealing with the fallout of that decision – has been “horrendous”, she says. “I guess I’m telling you all this story because it shows how complex the situation is, and how important the situation is, not only for the primary caregiver but for all the family members of someone who is living with dementia.”

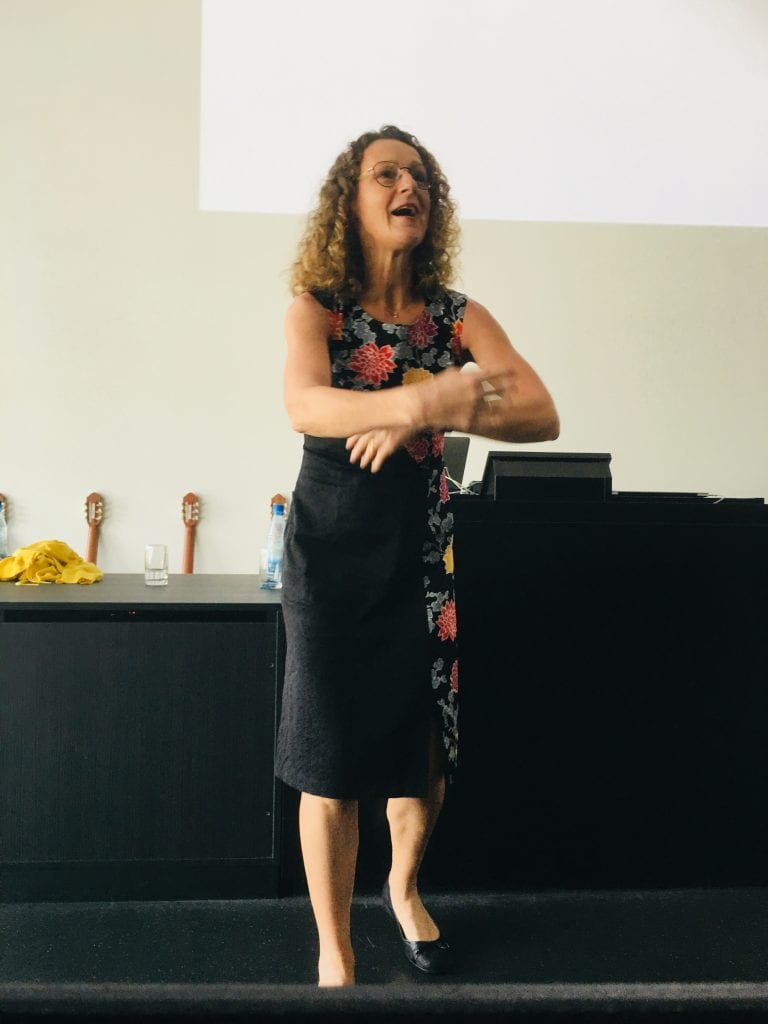

Clark concludes her presentation with a practical demonstration involving the song Belle Mama. She runs back and forth, instructs everyone on the left side of the room to start at one point, with one vocal line, those in the centre of the room to start at another, those on the right of the room yet another.

There’s laughter, a short rehearsal, more laughter, before everyone in attendance bursts into glorious song. Everyone’s body language has become more animated, there are smiles on most faces – it’s hard not to assume the exercise is good, in broad terms, for the brain.

Cue Dr Claire Lee, a post-doc researcher in Melbourne’s Music Therapy team, with a graduate diploma in Music Therapy and a PhD in neuropsychology. She’s co-presenting with Thomas Wosch and their first slide shows a cross-section of brain.

“This could be the most boring part of your day,” she says to laughter from the audience. “But I think all music therapists should keep up to date with research in neuroscience, psychology, and behavioural science. So even though this might be quite be boring, I’m going to provide a brief overview of different types of memory, because there are different types, and specifically about autobiographical memory.

“Why is it that people with Alzheimer’s or other types of dementia can still process music?” she asks. Even though they are densely amnesiac or can’t remember what they had for breakfast?”

It’s clearly not boring – the audience is rapt.

Among the people sitting outside enjoying the sun during the next break is Evan Williams from Newcastle, Australia. He graduated with a Bachelor of Music from the University of Melbourne’s Faculty of Fine Arts and Music in 2003, before moving to Hamburg the following year to continue his studies in French horn.

“I eventually ended up winning an audition for the orchestra in Würzburg,” he says,”which is why I ended up living here.”

He completed the Master in Music Therapy at FHWS in 2016, taking classes with Felicity Baker, among others – partially to give himself more freelance work options. “I already have the full-time orchestral job, which I’m enjoying, and a very young family, so my hands are full. But I’m still very interested in branching out.”

Music therapy, he says, offers something unique. “It’s just a fascinating field. The fact that you can use music to influence people’s health in positive ways is fantastic, and I get a lot out of working with people who don’t have much, or any, musical background.

“I’ve worked with children with disabilities and people with dementia, all of whom need empathetic people to work with them. For them, it’s very rewarding, but also for me, as the music therapist.”

The rewards for Wosch are equally apparent. His working relationship with Baker started in 2001 at the university of Sogn Og Fjordane in Sandane in Western Norway, where Baker had a position as a lecturer in music therapy – her first academic post before moving to The University of Queensland.

Following Wosch’s PhD, they worked together at the university, and their professional relationship has continued to grow since he began working at FHWS in 2008.

“As you know, Felicity has been coming here since 2009,” he says. “It’s a special collaboration we have with the Melbourne-Würzburg Dementia Songwriting Project, and now sharing PhD candidates, and so on, even though some of our students say, ‘It’s so far away – why Australia?’”

Which begs the obvious follow-up question: why not Australia?

“Music therapy, at the end of the day, is a small field,” says Wosch. “Elder care and dementia care are specialised fields within that, and we can see so many opportunities to cooperate with Melbourne.”

For Baker, the distance between the two countries is a secondary consideration – what matters is the work and its outcomes. “A couple of years ago, I was involved in a one-day research symposium in the States,” she says. “And so I flew there from Melbourne, arrived in the afternoon, attended the symposium and flew back to Melbourne the next day. Actually, I don’t recommend doing that.”

“But this trip, and the connection we have with Würzburg, is very special. Just look at today. Here we all are, talking about music therapy, and all the wonderful, important work going on.”