Against tokenism, towards nuanced representation: The future of the Australian screen according to four VCA filmmakers

Filmmakers and VCA Film and Television alum Caleb Ribates, Noora Niasari, Goran Stolevski and Matthew Victor Pastor say the Australian film industry must continue to evolve beyond ‘ticking diversity boxes’ to ever-more-meaningful inclusion. This is the only way Australian cinema can stand for its people.

“We’re seeing a push for representation on screen, but what type of representation is actually meaningful?”

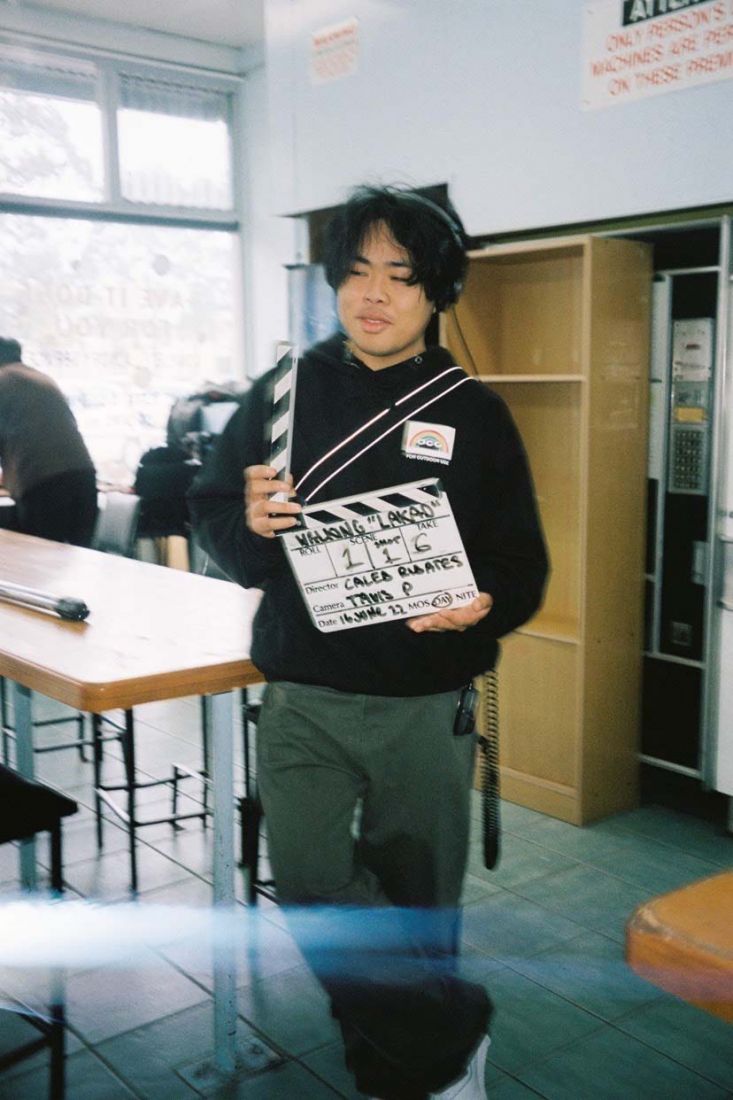

This is a question posed by 22 year-old Caleb Ribates, a recent Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) grad already making waves in the local filmmaking scene.

Caleb’s first feature-length film Anak, which tells the story of a Filipino-Australian father and son,premiered at MIFF 2022. The filmexplores questions about masculinity and the different experiences of first and second generation Filipino migrants in Australia.

“I really tried to explore the relationship between parents and children in Filipino households. And I would say this might be relevant to a lot of Asian households,” said Caleb.

In Anak Caleb tackles themes like the “cultural clash” he sees young people in his community grapple with.

“I wanted to talk about how past cultures and external cultures have been influencing our upcoming generations. We [second or third generation Filipino Australians] end up having this really weird mix of identities, and different types of struggles that are unique to our upbringing.”

“[There can even be] an absence of familiarity between a child and a parent, because of the difference in culture they’ve been brought up with. I want to explore this grey area.”

Anak also explores toxic masculinity in the relationship between its characters. Caleb is concerned that a lot of screen ‘representations’ of diaspora communities shy away from grappling with nuanced conversations which are actually relevant to them.

“We need to start acknowledging and telling stories that are more complex, that actually reflect matters of importance to our cultures and upbringings.”

Noora Niasari, a Tehran-born, Australian-raised filmmaker, who graduated from the VCA in 2015, agrees.

“We are behind when it comes to inclusive storytelling and partnerships with POC or other minority groups. The way artists are approached can often be tokenistic or exploitative,” she says.

Power, a genuine voice and agency

Niasari’s graduate short THE PHOENIX (Simorgh) won the VCA New Voice Award, was nominated for an Australian Directors Guild Award and was selected for the 2015 MIFF Accelerator Lab.

Niasari is currently in post-production on her debut feature film Shayda starring Zar Amir Ebrahimi (who won best actress at this year’s Cannes Film Festival for Holy Spider). Shayda follows a young Iranian mother and daughter seeking refuge in an Australian women’s shelter and will premiere next year at Sundance Film Festival. Niasari is also working on a much-anticipated feature film adaptation of Iranian-American novel RAYA.

“I notice that many filmmakers in my generation, especially POC, struggle with self-esteem and imposter syndrome. I think it’s because we have been told for so long that ‘we should be grateful’ for any opportunity offered to us,” she said.

Niasari, like many others in the industry, says this can be rectified by top-down structural changes, where gatekeepers open doors, “and keep the doors open for people of diverse backgrounds to take positions of power, to have a genuine voice, to have agency.”

This change is starting to happen in the industry, but it’s very slow.

I spoke to Goran Stolevski the day after he returned from a five day trip to Germany to accept an award for Best Feature at the International Film Festival Mannheim-Heidelberg for his debut You Won’t Be Alone. The film, a supernatural folk story set in a 19th century Macedonian village, acted in a Macedonian dialect, has received international acclaim. It has in Australia too, but in what Stolevski describes as a more “aesthetically conservative” industry, this has required more elbowing.

“I think there's a reality, a social reality that has created what the audience is for Australian cinema, that has only made a certain kind of film financially viable…. That has meant we ended up producing work that is a bit, well, conservative.”

The only way to change this conservatism in the industry is to support original and singular voices. Stolevski, who has risen to international success with films Of an Age and You Won’t Be Alone, with more on the way, has long been fantasising about a cultural shift in Australian cinema.

An Australian new wave?

“There have been periods in various countries at various times where a collective of artists have produced really exciting work. The most obvious is the French new wave, then there was the new German cinema in the '70s, and I would argue there was a Romanian new wave in the last 15-20 years, where multiple really interesting directors have done interesting work,” he said.

There are so many people in Australia producing original visions, he says. They just need to get more attention.

“If that were to keep going, it might amass into something that resembles what I'm talking about in terms of this collective of filmmakers."

Caleb Ribates and another alum from his cohort Matthew Victor Pastor, are part of one such newly formed collective of Australian-Filipino filmmakers.

Pastor says this collective, and films like Ribates’ Anak and The Plastic House by Cambodian-Australian filmmaker Allison Chhorn, have had a powerful effect on him.

“They create a framework which can encourage the next generation to tell screen stories from their perspective and keep screen culture alive.”

“I see so much talent in the short films that come out of film schools like VCA. That's where the future of our film culture is,” he said.

Pastor is counted among these many talented and successful VCA filmmaking alum. His Masters film I am Jupiter I am the Biggest Planet screened at over 20 international film festivals and his feature films The Neon Across the Ocean and A Pencil in the Jugular have since premiered internationally.

“We need more people who write what they know, and chances for people who look like me to be able to make smaller intimate features on personal topics. And of course, it’s always a matter of [access to] resources,” says Pastor.

Artists often cite community as the most valuable and interesting part of their practice. Niasari says the aspect of filmmaking she is most excited about in general, is the depth of human connections made through storytelling, “whether it is between cast, crew or with audiences - it's a beautiful thing.”

There is an incongruence when an industry which is ‘in the business’ of connection through storytelling, continues to have structural problems with inclusion. Many filmmakers have expressed frustration about working within this paradox, and for being exploited for their diversity rather than platformed to make their own creative decisions.

Senior lecturer in Film & TV Adrian Holmes says the VCA is focused on meaningfully amplifying the unique voices of its film students to counteract this.

“The film school has, I think, a really important role to play in the development of young film-makers, particularly those from cultures that have been excluded, misrepresented or exploited by an industry that has been famously exclusionary in its depiction of life in Australia,” he said.

“We’re deeply focused on working to provide opportunities for our students to find and refine their own film-making and storytelling perspectives through making their own work, their own stories in their own voice, allowing them to develop genuine confidence and self-belief in the essential value of their unique perspectives.”

He says the work of filmmakers like Caleb, Noora, Goran and Matthew is “vital, charged and connected to the world as it is”, and he credits them for their fierce energy and preparedness to challenge and reimagine the industry.

“Our students will become the industry, will own the industry, and there will be no place for the kind of gatekeeping and wilful ignorance that has characterised much of screen culture in Australia since it started. It’s so exciting to see these filmmakers getting out there and making such fantastic work, and supporting each other along the way,” said Holmes.

The success of these original voices in Australian cinema gives us the future story. In this story, Australian cinema has moved away from tokenism and towards nuanced and meaningful representation. The multiplicity of life experiences and creative visions in this place are celebrated, and funded.

Discover Film and TV at the VCA.