Cultivating a space for diverse voices in visual art at the VCA

For many artists, their art emerges through the creative process – by the artist following where the work leads. When higher education is increasingly viewed as a blend of knowledge-making and vocational training, how does an art school cultivate a space for diverse voices to thrive through this creative journey?

In a panel as part of the 2022 VCA Director’s Dialogue series, performance artist Stelarc re-iterated a theme that appears throughout his work:

“For a performance artist, ideas are easy – what’s difficult is to actualise those ideas. And the problem is that slippage occurs between your intention and the outcome.

“But in fact, that’s what art is: that slippage where you can incorporate the accidental, the unexpected.”

For Associate Professor Simone Slee, Head of Art at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA), the premise is similar.

“Artists start from who they are, and where they come from, and somewhere in this space an intention or an idea for an artwork is born. And then there is the process of making the artwork!”

For Simone this is an emergent messy process where “I think of my own process in making art: my job as the artist is to be curious and open, and to listen to the questions the artwork proposes, and follow where it needs to go”.

The responsibility of an art school is to create a safe space for its students to learn through this process of making – to be alive to the complex conditions that create our world.

“Sometimes this may also include how we, as the artists, personally connect to this complex world,” Simone says.

“We are always asking ourselves: how do we enable the opportunities for our students to test and trial their ideas to allow accidents and opportunities to occur so that artworks can emerge that surprise, generate discursiveness and reveal new understandings – for both us and the young artist that makes the work.”

‘Artists teaching artists’

This emergent methodology of artmaking can also enable multiple perspectives and a kaleidoscope of artistic expression, so each student at VCA Art can find their own voice.

The question of how to enable a multiplicity of voices and allow art to lead is one which drives visual art teaching and research supervision within the VCA.

“At VCA Art, we celebrate difference, where our students, researchers and colleagues are from diverse contexts – reaching from our First Nations colleagues to those that belong to diasporic communities and settler communities,” says Simone.

“We’re very mindful of the place on which we are so fortunate to work, where artists and the Traditional Owners of the land have created for thousands of generations, and the incredible opportunity we have to learn from our First Nations community.”

There isn’t a ‘house’ style at the VCA, says Simone – instead, there’s a great deal of diversity. There’s also more scope for what ‘art’ can be within the art institution compared to even 10–15 years ago.

“We have artists teaching emerging artists within an embedded studio environment. This is really key to what we do here. In many ways, the students are also leading us, particularly into that space of what it means to be running a diverse and inclusive and safe pedagogical environment. It’s a two-way dialogue.”

“We need students to be able to galvanise on the ground in a community,” says Simone.

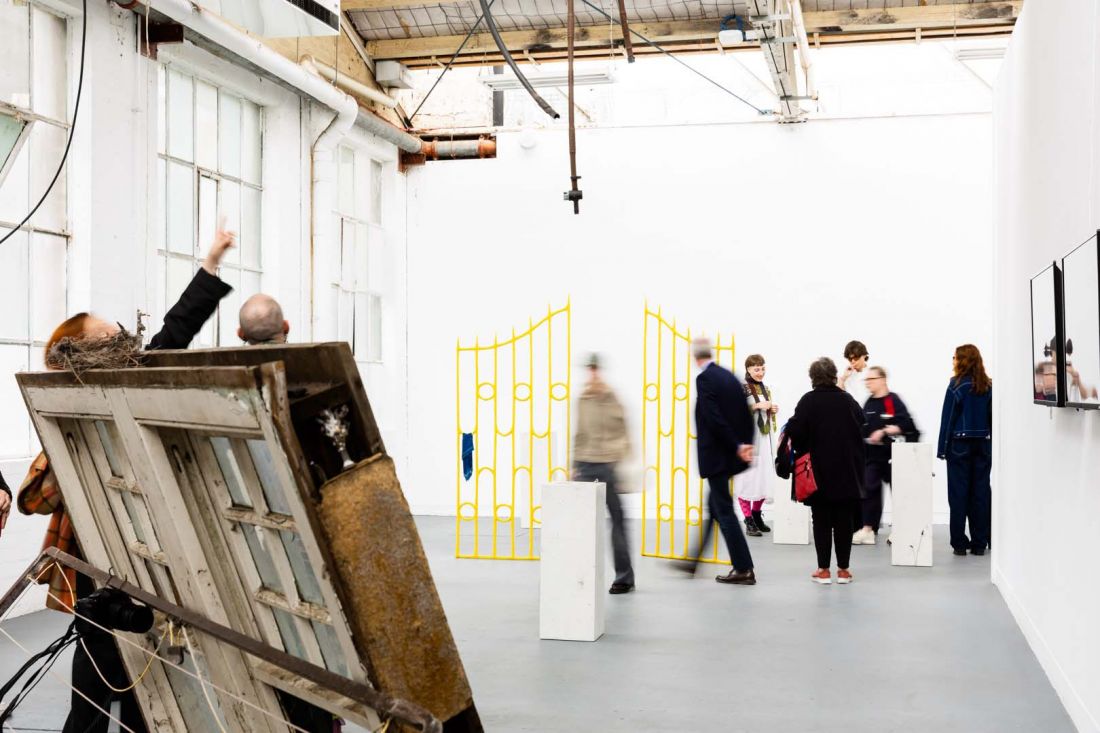

“The more we embrace opportunities for students and our art colleagues to collectivise – such as through workshops and exhibitions, magazine production and art groups – the more we can foster a healthy space for art to emerge.”

Watch a video walkthrough of the Visual Art Grad Show 2022.

Ultimately, working with students and researchers to unlock the future of visual art offers parallels with the act of artmaking itself. A major part of the practitioner’s role is to listen and respond: to bring together materials and vision, to begin the process, and – as the outcome presents itself – to help uncover it.

“Learning to sit with discomfort, in that listening space, to be curious in the face of uncertainty and to discover unexpected outcomes is one methodology in becoming an artist – a skill set that is absolutely central for our complex and unknown future that can also build diverse voices and approaches to thinking about our world,” says Simone.

She draws parallels between the emergent process of artmaking with principles often applied by strategists in volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous contexts – the understanding that “potent and creative solutions are often emergent and diverse, rather than premeditated and singular”.

The perception of universities as knowledge-makers toward specific vocations is dominant in broader Australian culture – even to the point of shaping government support for study in specific fields.

But a reductive notion of education is exactly what Visual Art at the VCA hopes to counter. Having the privilege of entering an art school in a university environment that values the production of culture is essential to creating global citizens with critical thinking and creative solutions to producing a future world. Strangely, art has a capacity to often predict and even create future worlds – and give us ways to understand and process the world we live in.

Watch a discussion from the VCA Director’s Dialogues series.

‘Our capacities for coming together’

For PhD candidate Linda Tegg, the acts of operating in association with an art school and of collaborating on her works, which include large-scale installations in public spaces, exemplify the process of allowing space for a solution to uncover itself.

With work that looks to collapse the divide between the human and the natural world, offering concrete alternatives to how we make space for life in urban environments, these acts of collaboration have deep significance beyond Linda’s art.

“My work is never made alone – I’m always working ‘with’.

“The circumstance of each work is unique as it comes together through a myriad of unique collaborations with people, places, organisations, and plants. This mode of working has taught me a great deal about our capacities for coming together to make a new reality.”

In particular, Linda acknowledges the role of the VCA as a community.

“Because of the studios and community, I know artists at every career stage and feel excited for art through the many interactions we have around my artwork and theirs,” she says.

“Being an artist is such a specific and often precarious way of being in the world and I am hugely grateful to my artist supervisors for supporting me in navigating this terrain.”

Knowledge-making and the institution

Meanwhile, for Therese Keogh, who describes the opportunity to do her PhD as “a joy and a gift”, the relationship between art, the artist and the institution is core to our social response to the climate crisis, which is, in part, the focus of her PhD research.

“What onus is on the individual researcher or artist to be doing the work that the institution should be doing?”

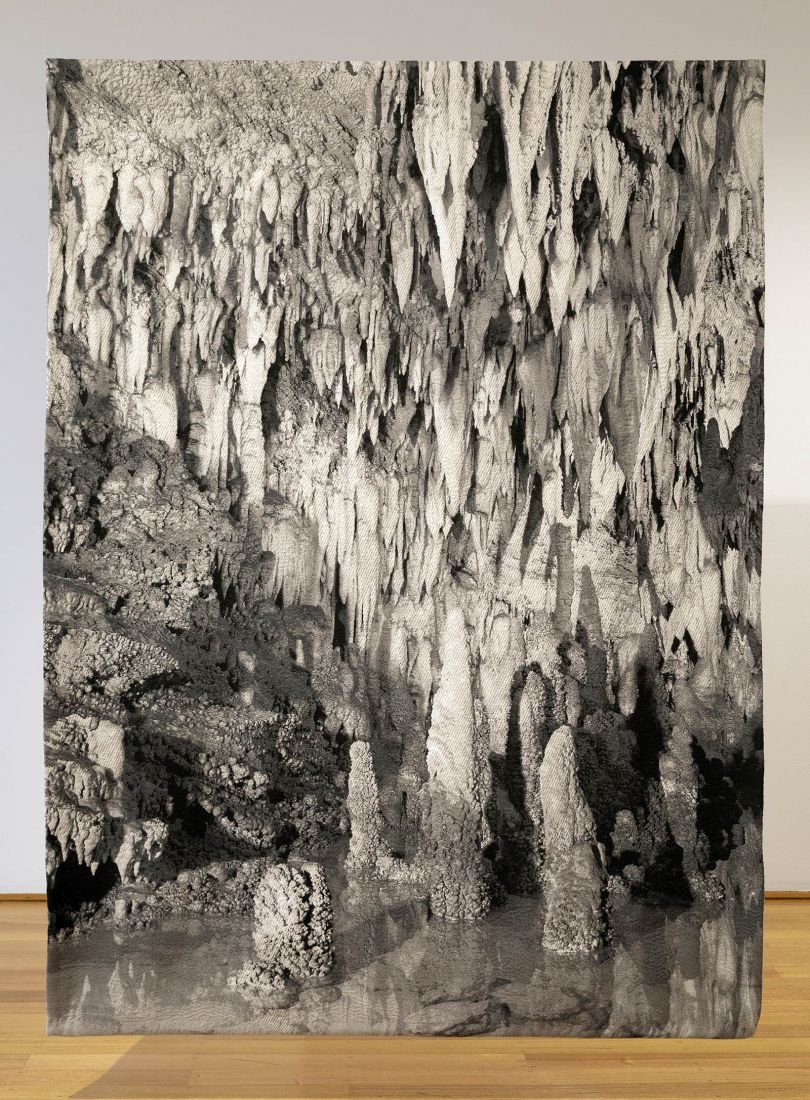

As an artist with an academic background in geography, Therese’s work in writing, sculpture and materiality explores disciplinary ways of responding to space and place – a task which brings together PhD supervisors from the VCA, the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne, and Queen Mary University in London.

Her PhD project in particular looks at the histories of coal extraction and coal trade in the development of Australia as a nation-state, and the geographical features that have been produced through acts like mining and dredging. Inevitably, this research confronts Australia’s entanglements with colonialism – which in turn raises questions of the history and modern role of the university.

“The contemporary university – the academy – came out of a post-Enlightenment era of knowledge-making, and contemporary disciplines have their origins in this space,” she says.

“But some art schools in Australia have a different lineage, where they came from technical colleges that then became contemporary art schools, and some got absorbed into universities – so they’re undergoing a process of becoming disciplined.

“So I’m interested in thinking about ways of writing that are undoing some of those kinds of work that come through conventions of academia – developing methods of narrative writing in an academy.”

Community voices and knowledge

For VCA alum Ashley Perry, these ongoing questions of privilege and access and systems of making and storing knowledge are also central drivers behind his work.

A Goenpul artist from Quandamooka Country (now known as Moreton Bay, Queensland), his recent works come from research into Quandamooka cultural practices with a focus on material culture held in museums, universities and private collections.

“It comes down to a privileging of knowledges and expertise – privileging a curator or anthropologist over what knowledge is held in the community,” he says.

“These institutions hold items for research purposes, but many of them lie dormant until a community member forks out the money to access them.”

Crucially, when that access is enabled, the value of community knowledge comes into its own.

“I’ve been looking at this particular collection of woven baskets – they had some exhibits attributed to Quandamooka Country. But looking at those baskets, members of the Quandamooka community who have weaving knowledge would be able to look at it, and through that style and those materials – they’d know it’s not from that Country,” he says.

“There’s a lot we can be grateful for about museums having those objects for communities to access today, but we need to reflect how time-sensitive access can be.

“A lot of Elders who grew up in missions, the people who had access to that knowledge as children, are now very old and passing away. It’s so time-sensitive that museums actually work with community to give access and create space.”

Making art is a transformational process: a physical act for the art that is made, and a mental reconfiguration for the artist who makes it and the people who experience it.

The VCA provides a unique student-led environment, where each individual can discover their own voice and where their artwork can lead them. As we celebrate our fiftieth year and prepare for our next 50, we’re eager to see where the years lead us – and we’ll always be at the front of conversations about what art can do, and how institutions can adapt, to help guide us all in a changing world.