An interview with Tom Crago, the artist behind Materials at the NGV Triennial

He’s the CEO of Australian video game developer Tantalus Media, a restaurant owner, a former triple-jump champion, a PhD candidate … oh, and an artist at the blockbuster NGV Triennial exhibition.

By Paul Dalgarno

Hi Tom, your virtual reality art exhibit Materials is currently showing as part of the international Triennial exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, alongside work by more than 100 artists and designers from 32 countries. What can people expect from it?

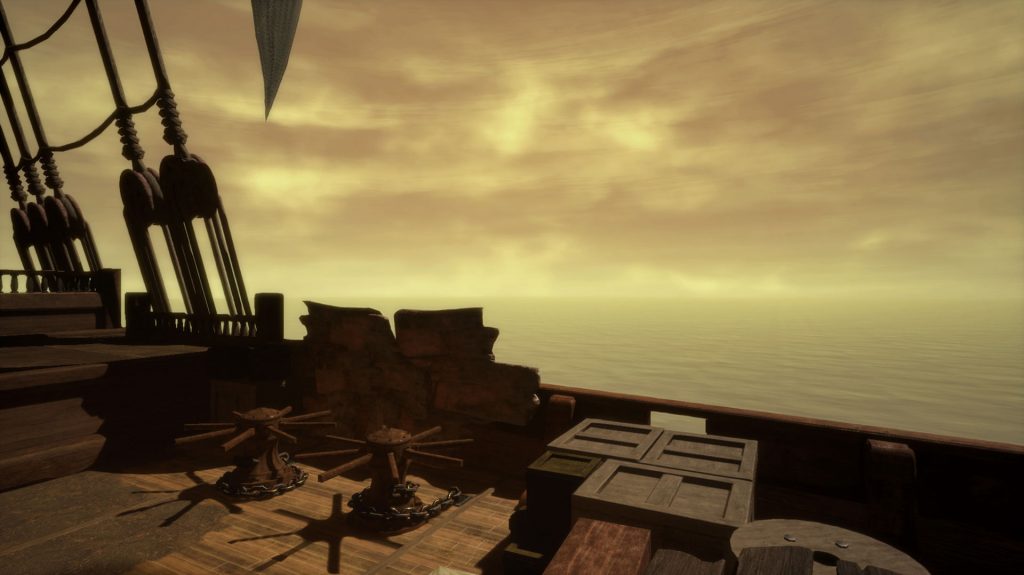

Materials is a virtual reality experience that takes place on a ship at sea. It’s a bit like a video game, but aims to occupy a space that’s more art-led and reflective.

Where did the idea come from?

Well, this is the first time I’ve done anything that resembles an art project and the story starts more than six years ago. At that point, I’d been making video games for about ten years through my company Tantalus Media, working with the likes of Nintendo and Disney, which was great. But I became mildly disillusioned with the world of video games and wanted to make a contribution that was little more personal. And I wanted to collaborate with artists who weren’t from my industry.

I started to look around to figure out where I could do that, and I stumbled across this school at the Victorian College of the Arts called the Centre for Ideas, and I remember looking at the information on the website and thinking: How extraordinary, how can this be real? A place within an arts institution that is itself a school of philosophy.

I sent an email to the VCA and set up a meeting to talk about the potential for collaboration, and ended up being offered the chance to do the project as part of a PhD there. That’s when I started working on it in earnest.

Among the artists I collaborated with at the VCA, and who added hugely to the project, were Mark Rodda, Viv Miller, Kate Tucker, Indigo O’Rouke and William Mackinnon. The audio design and composition is by the VCA’s David Shea.

I’m guessing you had no idea that it would eventually be part of an international survey of contemporary art?

That’s right – the Triennial was a glint in nobody’s eye at that point. I started working on Materials in my studio and at the VCA and a couple of the curators at the NGV became aware of it through their association with the College. They called me in for a meeting two years ago and asked if I’d like to think about putting it in the Triennial, and I said sure.

Have you been hanging out secretly at the NGV while people are playing Materials to see how it’s going?

I go into the NGV to do lectures and talk to students and do presentations, so I’m in there pretty regularly, and, yeah I do sit and watch people have the experience and observe them emerging from it, back into the real world. We also have some fairly sophisticated analytic software within the experience. It’s all anonymous but I know how long people play for, how many people are playing at a given time, and so on.

From this, I can tell where people stumble or where they stop playing or, perhaps, if they’re more eager to explore. Even though Materials, by design, is an extremely solitary experience, and is in a sense about isolation, I want as many people as possible to participate in it and ideally to get as far as possible through the experience.

I have to say, I did it the other day and I loved it for ten minutes then found myself getting quite motion sick, so I stopped for a second and put the headset back on, and then felt sick again and had to stop completely …

That’s very common and a little bit of residual nausea is part of the experience. Some people experience that more profoundly than others while some people won’t experience it at all. So that’s another thing I keenly watch and observe. Interestingly, no-one under the age of 18 seems to suffer from motion sickness while playing it although maybe that’s just because mostly they’ve had more experience with virtual reality.

And so you have your PhD now?

No, I don’t. Materials is the creative work component of the PhD but I still need to write my thesis. I’ve never had to do such a substantial piece of academic writing, so it’s mildly terrifying.

You have written a book, though, Flashbacks from the Flow Zone (2014). Can you tell us a little about that?

Well, I don’t know where it’s shelved in bookstores these days, but I consider it to be a travel book, as it’s really about my experiences travelling for business. Mostly it’s a love-letter to that fairly specific kind of travel, and maybe about “journeying” in general.

There were lots of stories that I wanted to tell that I’d been writing down for the last ten years, so the writing part was a joy. Editing and finishing the book once it had been picked up by a publisher was less enjoyable, and the toughest part of the project, but it got done in the end.

Embracing things you haven’t done before seems to be a driving force for you – is that fair to say?

I take a “slate” approach to life, I guess, where I’ve got a bunch of different projects on the go at any given point in time and can shift my focus from one to the other depending on how they’re going or what requires attention. I think it’s maybe a way of avoiding having to focus on any one thing for too long, or a means of removing the necessity of having a proper job.

Do you think that was always there? As a kid were you bouncing around from one thing to the next?

Yeah, absolutely.

And you also represented Australia in athletics and were Pacific Games Champion and State Champion in the triple jump?

Yeah, that’s right. Athletics was the most important thing in my life for ten years, from the age of 14, all the way through the latter years of high school and all through university. Unfortunately, I never achieved my goal in athletics, which was to make an Olympic team, so I finished my involvement with the sport pretty disappointed about that. But I was able to move immediately onto another project, which was the world of video games.

Were video games already part of your life by that stage?

At university, I thought I wanted to go into the film industry – that was my ambition. I didn’t realise there was such a thing as a video game industry in Australia. But when I did, games looked a lot more appealing than film, and more of a meritocracy. It was more dynamic – you didn’t have to earn your stripes to the same extent and it seemed to be just as creative. So I thought I’d have a crack at that and have never looked back.

You hold arts, business and law degrees. Were they done concurrently or one after the other?

Extending my period of study was initially about justifying my continued dedication to athletics, and buying myself some time to keep training. At the University of Adelaide you couldn’t get straight into Law, you had to first do a year of Arts or whatever, so I did that, then I got into Law, and did the two concurrently. I wanted to do Honours in Arts and in Politics but you couldn’t do that at the same time as Law, so I thought I might as well start a Business degree, but at a different University so no-one would know. Eventually I knocked off all three, after something like seven years.

Do you come from a family of entrepreneurs? Did you have a role model to follow?

No, not at all. My father was a high-school teacher and my mother was a healthcare professional. I don’t know where the entrepreneurial spirit came from, actually. I think maybe it was just a desire to work for myself and to be in control of my own destiny. More than anything, I’ve always wanted to live a creative life. Business kind of bores me to be honest; I’m not entrepreneurial in the sense that I get super excited about growing companies or making money or anything like that. I just want the freedom to do my own projects.

Last year you opened a 13-seat restaurant in Tokyo called OUT, that serves just one kind of truffle pasta and just one red wine to the soundtrack of Led Zeppelin’s album In Through the Out Door. That’s quite the project …

Yeah, that’s been the craziest of the lot. Again, it was just something I thought would be interesting, and that seemed like a good idea after a bottle or so of wine. Now I co-own three restaurants – OUT in Tokyo, and SPQR and The Mayfair here in Melbourne. I only took that plunge because my business partner [restaurateur David Mackintosh] has a great deal of experience running restaurants and knows what he’s doing, unlike me. It’s crazy in the sense that it’s different to my core competency, and a very unusual industry in it’s own right. But it’s an industry I love and have loved for a long time.

Are there any forthcoming projects you’re excited about?

I’d like to continue making games that have an artistic sensibility, given Materials is the first project I’ve done in that kind of genre. I’m doing more writing as well – I want to write another book, and I need to finish my PhD. Those are my priorities at the moment.

I’m guessing you don’t have a lot of downtime in your life? Or do you get some kind of relaxation from working on your many different ventures?

It’s funny, I look at friends of mine who are lawyers or accountants or whatever and their days are filled with all sorts of meetings and appointments. They lead a heavily-scheduled existence. I walk to get coffee three times a day for twenty minutes, I don’t have a lot of meetings, no-one calls me. There are very few prescriptive demands on my time.

It’s a very fortunate and privileged way of living. I never feel busy and I rarely feel stressed, and that means I have the space to think about the projects I want to focus on. The key for me is that the people who work in my companies take on most of the responsibilities. I’m hugely reliant on that and it gives me a terrific brand of freedom.