VCA Digital Archive: animation and diversity

The VCA Digital Archive is a living audiovisual record of student films that date back to 1966. The articles in this series respond thematically to the depth and breadth of the collection. Enjoy!

By Jean Tong

Along with many contemporary artists, I spend a lot of time contemplating “diversity” and its representation in the media we consume.

While we still barely scrape the surface of representation beyond tokenism and stereotypes, I do find myself musing on how this historical lack of representation has led us to the bind of a certain kind of literalism which stands in for the bulk of mainstream diversity. For example, women hated female stereotypes in Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), queer people protested tragic queer narratives in Love, Simon (2018), and invisibility of Asian representation in Crazy Rich Asians (2018) (Southeast Asians, anyway).

There’s nothing inherently wrong with these, but it makes me wonder if this mainstream take on diversity sometimes over-literalises who we see or who we can see ourselves reflected in, and under what circumstances?

I believe that the form of animation provides a kind of alternative to literalism. In animation, the illusion of movement and “aliveness” is evoked from a frame-by-frame process of absolute specificity, creating a world where the rules of physics, biology, sociology are inherently undone and remade at a rate of approximately 25 frames per second.

Here, the frame-to-frame gradations offer a space in which representation and literalism aren’t necessarily related, offering us the opportunity to understand “diversity” and empathy in a more nuanced manner.

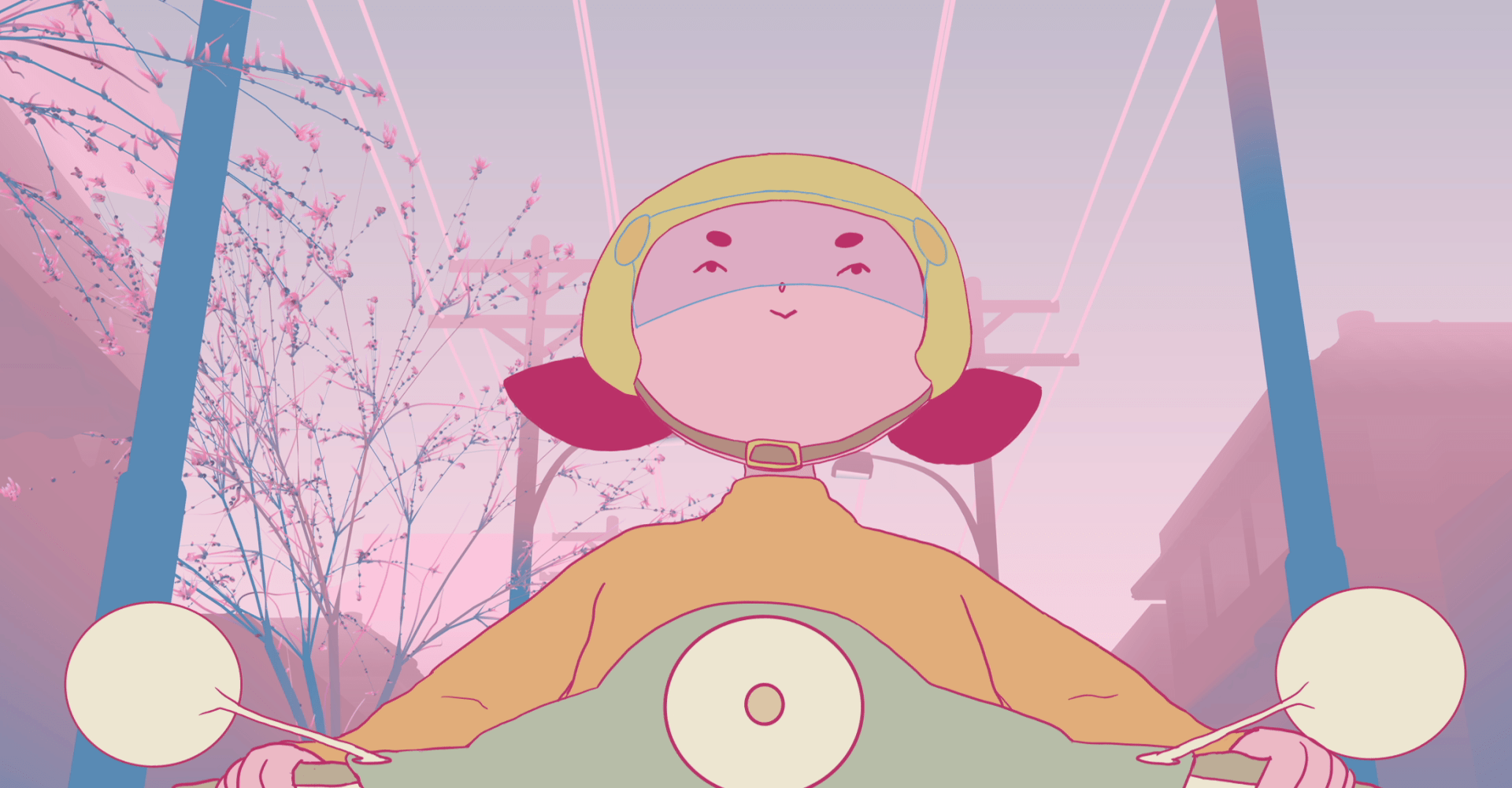

Bear in Mind. Tiffany Goh. 2016. Animation.

In Tiffany Goh’s Bear in Mind (2016), a girl visually morphs from person to bear and back again while at work. Unlike in Kafka’s Metamorphosis, it is ambiguous if the girl’s metamorphosis is visible to others or a symptom of her own perception of self.

Goh’s shape-shifting world of thin strokes and beautifully thoughtful scrawls call into notice the act of being made – of being drawn and created and depicted in real time, allowing real and present transmutation; immediate changes. I am reminded not only of the thinness of the boundary between my identity and my physicality but also the lack of necessity for one thing to look like that thing in order to feel like a thing.

This illustrated metaphor presents the morphing lines and frame-by-frame uncertainty of how the form one takes versus how one is seen changes in every given moment, suggesting an alternative mode through which we might overcome cognitive biases relating to physical traits. You are not a bear. But perhaps this can be you too, perhaps you feel this liminality of skin too.

Touch. Lauren Edson. 2015. Animation.

Though we’re aware that our skin separates ourselves from the rest of the world, this separation is something we rarely think about. Lauren Edson’s Touch (2015) gently calls to attention this separation of person and the world through a thick blue boundary which envelops a character experiencing PTSD from implied sexual assault. Intrusive touch has caused a breach of the self, and the emphasis on the bodies’ borders speak to a hyperawareness about how touch has intruded on these once-safe borders.

Edson’s animation capitalises on the form’s ability to bring to life spontaneity of expression without compromising on abstractness. Rather, the feeling of an emotion as such (such as the shockwaves and bursts of colour in Edson’s animation) can be shown exactly, circumventing the need for a single live-action performer to deliver on an emotional performance encapsulating all of those feelings.

Bucket Head. Daniel Hartney. 2001. Animation.

Animation as a technique allows for visual representations of symbolic or simplified references; the direct referents allow viewers to bypass their “analytical” brain and avoid over-intellectualising what’s being shown. In Daniel Hartney’s Bucket Head (2001), a robot with a bucket as its head lives in a future where it has been invented to keep the streets clean.

Through the lack of people depicted in the animation, we’re invited to consider humanity’s disregard for waste management without any expectation of an “appropriate” intellectual response to the socio-political content. Again, this is achieved without a literalisation of having to watch people agonise over waste management (such as in Pixar’s Wall-E, which similarly features a robot in charge of cleaning up Earth).

Overgrow. Jennifer Crow. 2015. Animation.

Similarly, in Jennifer Crow’s Overgrow (2015), a homophobic socio-political context is implied through the depiction of witches in a contemporary society – a nod, obviously, towards the Salem witch hunts, which condemned innocent women out of fear of the unknown. The witch’s coded queerness allows the viewer to get closer to the “feeling” of being a marginalised outsider without invoking any preconceived understandings of contemporary politics.

Good Grief. Fiona Dalwood. 2012. Animation. Documentary.

Animation can also invite unexpected emotional investment, as skilfully demonstrated in Fiona Dalwood’s award-winning stop-motion Good Grief (2011). The clay animals are “voiced” by individuals musing on their personal experiences of loss. The stop-motion creates a distancing effect by bringing clay animals to life, using the unexpectedness of the clay animal’s charm to disarm us enough to be able to engage with profound grief.

On an international scale, animation’s ability to profoundly engage viewers can also be viewed in Andrew Goldsmith & Bradley Slabe’s Lost & Found (2018), a local short animation about a crocheted fox and dinosaur which recently nabbed a spot on the Oscar shortlist for Short Film (Animated). This particular example highlights the possibilities inherent in all the featured animations here – through its very genre and conventions, animation provokes our strange and greedy desires to project ourselves onto something unfamiliar.

It seems that the more alien the world and the characters in the animation, the easier it can conversely become, for us, to attach greater familiarity and significance to it. The vulnerabilities animation opens up can emphasise what art can do to bridge differences between people in a contemporary world.

Jean Tong is a Melbourne-based writer and dramaturg. Her work has been performed at Melbourne Theatre Company (Hungry Ghosts) and The Coopers Malthouse (Romeo Is Not The Only Fruit); published in Peril Magazine and Meanjin (Spike), and presented at the Emerging Writers’ Festival. In 2018 she was selected for Screen Australia’s ‘Developing the Developer’ workshop and for Film Victoria’s TV and Online Concept lab (Plot Twist). Visit Jean’s website.

The VCA Digital Archive series of articles was commissioned as part of a grant from the University of Melbourne, Student Services Amenities Fee. University of Melbourne staff and students and some industry people dipped into the FTV archive and watched films based on themes. The idea was to use the archive as stimulus to curate and create. Some responses are completely creative, others are reviews, others are word art pieces.

The full collection will be available for research from mid-2019. In the meantime you can find a selection of more than 100 films live on our YouTube page. To find out more, visit the VCA Digital Archive Project Page.