VCA Digital Archive: #Metoo and the myth of male genius

The VCA Digital Archive is a living audiovisual record of student films that date back to 1966. The articles in this series respond thematically to the depth and breadth of the collection. Enjoy!

By Ivana Brehas

Sunday Emerson Gullifer’s dazzling short film tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow(2018), examines the physical and psychological damage inflicted on people (particularly women) in the art world as a consequence of the male “genius” myth. The way this myth is used to excuse abusive behaviour is extremely pertinent in today’s wider cultural context, with numerous movements like #MeToo and Time’s Up bringing these issues into the spotlight.

Its premise is simple and familiar — a group of actors put on a play (in this case Macbeth), directed by a tyrannical asshole — but its execution is uniquely poetic. The film focuses on Lizzie (Matilda Ridgway) – an actress whose dream role isn’t Lady Macbeth, but Macbeth himself — and the brutal mistreatment she experiences at the hands of director Helmut (Mark Leonard Winter).

Helmut’s provocative vocabulary and vaguely Danish accent calls to mind real-world enfants terribles such as Nicolas Winding Refn. “[This is] a Helmut show,” he says. “It’s about power. It’s about ambition. It’s about sex… It will be brutal, it will be violent, it will be bloody, it will be beautiful, and like nothing that you have ever seen before”.

He uses this language to construct an image of himself as a transgressive and boundary-pushing artist, and significantly, an auteur — the play is a “Helmut show”, defined by his authorship.

There are subtle comments on generational wisdom here — the older, more experienced actresses are more cynical about Helmut than the young Olivia (Charlotte Nicdao), who still buys into the myth of his genius. But the older women do not voice their criticisms to Helmut himself — only expressing them in the safe, private context of the women’s dressing room.

They remain silent as he mistreats them, and there is a sense of resignation — an acceptance that this is simply “how things are”. It would not be a great leap to assume that they have encountered many other megalomaniacal directors before Helmut.

Gullifer’s script also hints at the ways women can feel trapped within a difficult industry. Snippets of Lizzie’s disappointed phone-calls with her agent imply that she’s struggled to find steady work. When she breaks down crying over her experience on Helmut’s Macbeth, she keeps repeating the phrase “it’s a job”, as if she feels ashamed for complaining. Economic desperation prevents many women from demanding better treatment in their workplaces and through the inclusion of such scenes, Gullifer blends feminist and socio-economic commentaries.

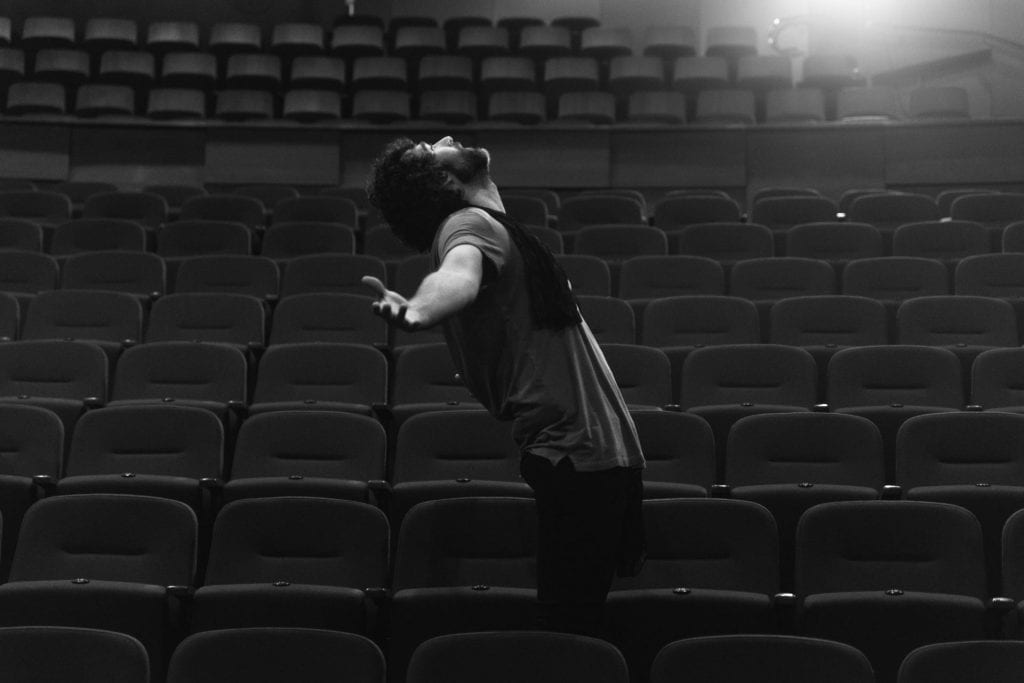

But perhaps most of all, tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow is a film about the body. The camera lingers on bruises and scenes are drawn out to focus on physical movement, inviting contemplation about bodily autonomy.

The theatre setting allows Gullifer to put Lizzie in a position of being treated as a literal “prop”. In a particularly disquieting scene, Helmut grabs and hits Lizzie’s body during a rehearsal, ostensibly demonstrating fight choreography. He smacks her stomach and bends her arm back, never once warning or asking her. He speaks to the male actors as if she isn’t there: “I do not give a fuck about her.”

Helmut’s perception of Lizzie’s body as a tool for his manipulation reflects the way women’s bodily autonomy is denied and ignored more broadly. The sense of female-body-as-puppet will be painfully resonant to female viewers who have been in similar situations as Lizzie — disembodied, watching with a curious detachment as their bodies become passive and yielding to the actions of men.

The film’s title (a Macbeth reference) suggests a Sisyphean relentlessness, and indeed, Lizzie is worn down by repetition. Night after night, she endures the same humiliation and pain, knowing that tomorrow (and tomorrow, and tomorrow) more of the same awaits her. Backstage, through tears, she states a simple, sorrowful truth: “It shouldn’t be like this.”

The film’s final scene, then, can be read as Lizzie’s reclamation of her body. In a beautifully shot a sequence by cinematographer Jack McAvoy, Lizzie wrests back control by pulling the puppet strings herself, so to speak.

The dream-like final moments call to mind a “revenge of the directed” in the vein of Josephine Decker’s Madeline’s Madeline (2018). Here, violence is transformed into dance, and Lizzie makes herself an active agent. Again, theatre can be read as metaphorical, as she must choose to break from the script — both the literal action of the play text, and the figurative societal “script” of female submissiveness — in order to liberate herself.

Ridgway is captivating to watch, incandescent in both senses of the word: filled with rage and emitting light.

Ivana Brehas is a Melbourne-based writer with a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Screenwriting) from the Victorian College of the Arts. She is currently completing a Master of Creative Writing, Publishing and Editing at The University of Melbourne.

The VCA Digital Archive series of articles was commissioned as part of a grant from the University of Melbourne, Student Services Amenities Fee. University of Melbourne staff and students and some industry people dipped into the FTV archive and watched films based on themes. The idea was to use the archive as stimulus to curate and create. Some responses are completely creative, others are reviews, others are word art pieces.

The full collection will be available for research from mid-2019. In the meantime you can find a selection of more than 100 films live on our YouTube page. To find out more, visit the VCA Digital Archive Project Page.