Conversations on Country: experiencing Indigenous cultural and creative practices with the Wilin Centre

Each year, the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development takes University of Melbourne students out on Country. Mireille Stahle joined the team in Yorta Yorta Country for a deep dive into Indigenous cultures and artistic practices.

By Mireille Stahle

It's a cool, bright day in the bushland reserve. Yorta Yorta Dja Dja Wurrung man Tiriki Onus, Head of the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development at the University of Melbourne and Associate Dean of Indigenous Development at the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, welcomes us to his grandmother’s Country – Yorta Yorta Country, incorporating greater Shepparton and Mooroopna and stretching into NSW across the Dhungala (Murray River).

We are standing on soft grass. Students are barefoot. Beneath Onus’ baritone you can hear the murmuring of gum trees. “I feel that my head works better here than anywhere else,” Onus reflects. “I understand things more. And, when I have been faced with difficult life choices, coming here gives me a certain degree of clarity about what's important. There's a feeling of safety here that I don't have necessarily anywhere else. I'm calmer. My thoughts have got more license in this kind of quiet.”

I have come here from Melbourne for a week, with a cohort of students from the University of Melbourne's breadth subject Ancient and Contemporary Indigenous Arts, to learn from ancient knowledge systems, and engage with more than 2,500 generations of cultural practice. The course is run twice a year in winter and summer and is one of a number of breadth subjects run by the Wilin Centre and available to most Bachelor students at the University of Melbourne.

Students from fields as diverse as science and Interactive Composition are invited to engage with Indigenous art forms such as Djekoga (net weaving), bundling feathers for Til-bur-nin (emu skirts), and sewing skins for a Biganga (possum cloak). Lauren Gower, pairrebeenne trawlwoolway woman and Wilin Centre lecturer, runs additional workshops to facilitate meditation and reflection.

Gower explains the importance of being on Country to engage in this kind of learning. She is quick to remind me that one is always on country. “You know that it’s different – but trying to describe the difference …" she reflects on the feeling of returning to her ancestral country, "if you think of it in terms of listening to a place, you’re having a different conversation. The conversation you have is more personal, you can hear what your ancestors are telling you."

When Onus finishes his welcome, the party of 17 disband amongst the trees – widely spaced, sheltering meadows of grass and wildflowers. This is part of Gower’s process of “arrival”. Some students race off, others stand very still. “The point of the exercise is actually stillness,” says Gower, “even when you’re moving – stopping to arrive in Yorta Yorta Country creates the mental space to pause and reflect”.

For many of the students it is the first time they have been encouraged to think about themselves in the context of land that is already rich with history. Even wearing shoes feels somehow sacrilegious. The Dookie Bushland Reserve – part of the University of Melbourne's Dookie Campus – is the largest of its kind on an Australian university campus and its vegetation was once common across the Riverine Plains of Northern Victoria and Southern New South Wales.

Dharug woman and Bachelor of Arts (Art History) student Jessica Alderton describes the experience of walking on the reserve: “I felt more at home and comfortable being out here in the bush, knowing that I am welcome here.”

I feel minuscule in the shadow of the tallest gum. It is nearly the height of the Arc de Triomphe, and arguably more beautiful. Feeling insignificant is an important part of the arrival process – it helps us to understand that we are just a few among many. Typically, we place so much importance on ourselves and our voices in the landscape that we can lose sight of the big picture.

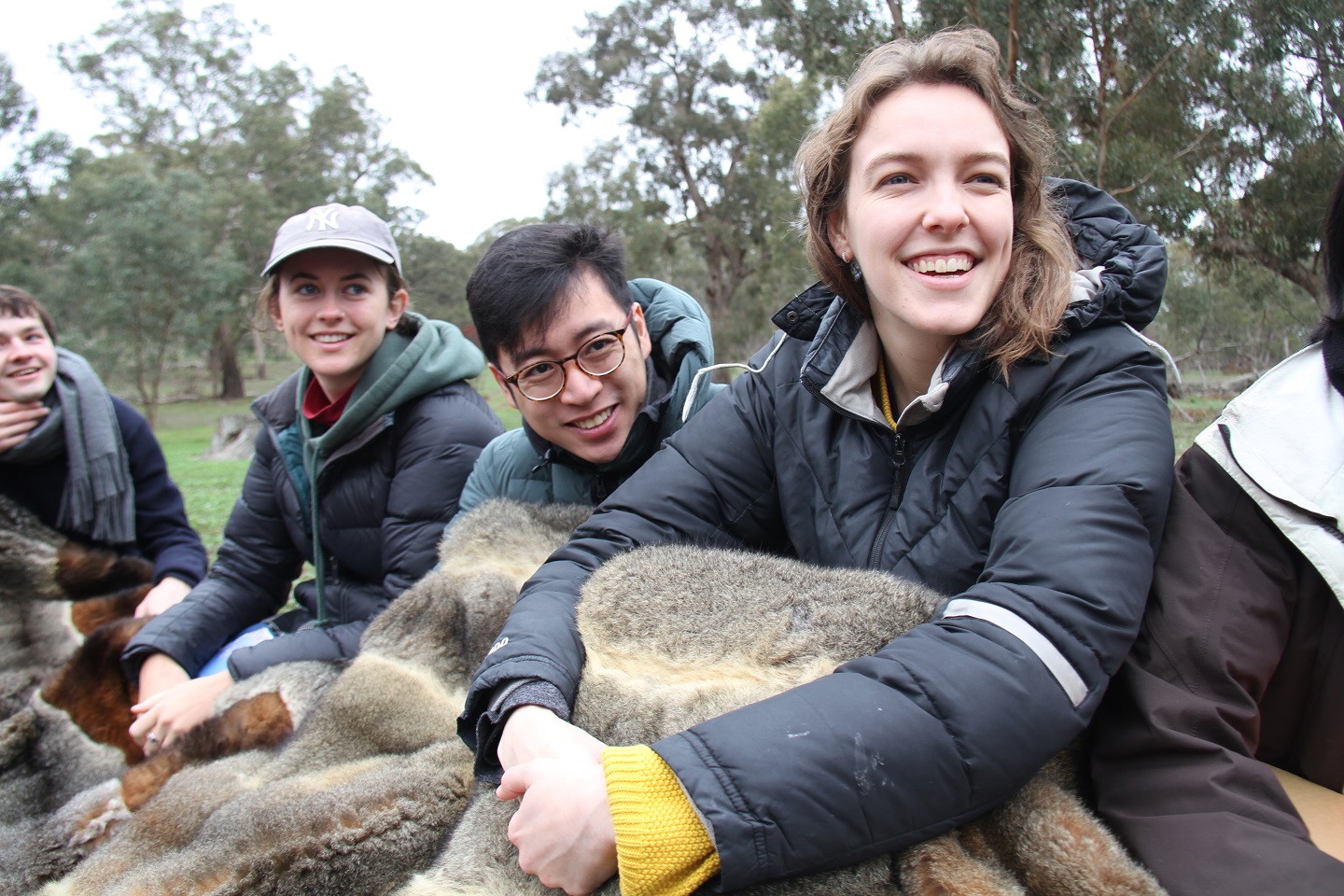

We revisit the bushland reserve many times over the week. Whether it be huddled together, talking quietly under a tarp, or moving stiff, cold fingers in and out as fishing nets begin to take shape between bowed trees. Onus, when he talks, is both revered and irreverent – his gregariousness stirs an almost religious admiration from his students. There is a lot of laughter.

Hiding from foul weather in the warm confines of the carpeted mess-hall, Onus lays a dozen possum skins on the floor. Making a cloak such as this Biganga is about reviving and reclaiming our traditional practices, he explains. It’s the epitome of community-based practice. I watch it play out before my eyes: students gather around and give sewing advice, holding seams steady. They help each other, chatting – students from different backgrounds, different parts of the University, sharing stories and stitching.

For Bachelor of Commerce student Felix Tan, the kinds of conversations had on Country were a highlight because, in his words, “these are the kind of things you will not be able to find in libraries or books, or in textbooks. These are from the heart, these are genuine and sincere”.

This contemporary homage to the traditional cloak, while created with polyester thread and steel needles, concerns itself less with its function, as it does with the fact that it is made by a community. Onus trusts the students to help him stitch the cloak for this exact reason – beyond just sewing skins together – “the cloak really lives in the relationships that are created between the people in the room. That's the important part.”

That’s what the Wilin Centre is all about. Outside its teaching and learning responsibilities, the critical work it does creating pathways into the arts for First Nations people nationally, the Wilin Centre also creates spaces and moments for University of Melbourne staff and students to exchange stories, knowledges and opportunities to be better community members.

Find out more about the Wilin Centre's Ancient and Contemporary Indigenous Art program, and about the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development.

In 2020 the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music will open a new Wilin Centre on the University of Melbourne's Southbank campus. Keep an eye on the Faculty Events page to see Wilin’s schedule of public events.

An acknowledgement from the author: I was born on Wurundjeri Country near the Birrarung. On Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung Country I was educated, and I work on the land of the Yalukut-Wilam clan. I have benefited from the generosity of the Yorta Yorta and Taungurung Countries where I have built on my own stories, and learned from the continuing culture of First Nations knowledge and arts practice. For this I am eternally grateful.

For over 2,000 generations First Nations people have sung their songs, danced their dances and poured their stories into this Country, and I would like to pay my respect to the leadership and stories of their Elders, past, present and emerging.