101 Sensations: on tour with the University of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in Asia

Between 23 September and 29 September 2018, the University of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra performed in Singapore and Shanghai, the first time it had ever travelled overseas. This is the story of that tour.

By Paul Dalgarno.

Before the week is out at least seven University of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra players will be standing on a bar dancing to cheesy pop music in a Mexican-themed nightclub in Shanghai; others will be cheering them from below; the road crew and professional staff will be busting moves to the Macarena; and I’ll be in a conga line, snaking around the upstairs bar holding Conservatorium Director Gary McPherson’s waist, with Faculty Dean Barry Conyngham close behind. But that’s not how the week began.

SUNDAY 10.38AM

I find the filmmaker for the tour, Gregory Erdstein, in the foyer of Melba Hall, Parkville, amid a sea of Asia Tour T-shirts (“One passion, many destinations”), violin cases, cello cases, backpacks and suitcases. Some 101 of the University’s orchestral musicians are taking part in the tour, none of whom – I hope – will catch the vicious head cold I’ve been trying to shake for a week.

My nose is blocked, my ears are blocked, I’ve coughed up things no squeamish person should ever have to see. I considered piking out of the tour by email – Re: Why I can’t come, soz – considered what that would mean for my career and standing in the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, decided against it.

My job is to document the orchestra’s first ever international tour in words, on film, to observe and ask questions for as long as humanly possible.

“I’m sorry, could you keep the noise down?” says a man with a knitted brow. There’s a morning concert being performed at Melba and the tour players are excitedly chatting. The hubbub dies down, simmers, starts boiling again.

The orchestra played its first concert of the tour at the Melbourne Recital Centre on Friday evening. It was fun, I hear a couple of players saying, although one young man is unsure about the condition of his instrument. Erdstein is already filming, and my nose is refilling, as it has been for days.

“What if I make someone sick?” I say to him. “That’s going to ruin their tour.”

“Yeah, it should be fine,” he says, moving away from me.

“It’s just that—”

A door opens. “Sorry, everyone, could you please keep it down,” says the man from the concert hall. “We’re trying to perform here. Is there any way you could, you know, go and wait outside?”

SUNDAY 3.57PM

We’re on a Singapore Airlines plane, the second of two carrying tour staff and players to Singapore. Edwina Dethridge, the Orchestra and Wind Symphony Coordinator, has shepherded us on and off the bus, through security, into the waiting lounge and onto the aircraft.

Three seats in front of me, I can see Head of Orchestral Studies and tour conductor Richard Davis in a casual shirt; Erdstein is two seats behind me, to the left; Peter Barron, the Faculty’s Development Manager, is five rows ahead in an aisle seat watching a film called The Escape; students wearing tour T-shirts are dotted around, interspersed with civilians. Cello cases take up a line of window seats, strapped in like Cluedo figures next to their owners.

The two young people sitting next to me are wearing casual clothes and speaking what sounds like Lithuanian. They may be part of the orchestra; they may be tourists. I could ask them, I have six and a half hours to kill and need to get the ball rolling with interviews. But I’m trying not to breathe on them, on anyone, on the plane.

SUNDAY 11.26PM

Erdstein and I get off the bus first, stand outside Singapore’s Peninsula Excelsior hotel in the darkness in what feels like 99% humidity. It’s 1.26am back in Melbourne. The players get off, smiling, search through the assembled suitcases for their gear while Erdstein films them and I try not to look like a sick person whose ears popped during landing and may never be the same again.

“Okay, so, listen, listen,” says Dethridge. “We’re going to Level Five. Level Five, everyone. Is that clear?”

James Hutchinson from Infrastructure and Operations is on Level Five. He came over on the first plane, looks fresh as a daisy, explains to everyone that we have snack packs – sandwiches and a cut-up apple I can’t look at without feeling nauseous – explains where our door cards are.

Hutchinson, in my interactions with him, has always been the personification of grace under pressure. His job over the last 18 months at least has involved much of the logistics of the tour, the macro, the micro, last-minute changes, passports and visas, student wellbeing, staff wellbeing – he’s been across it, hasn’t looked pissed off even once. I’m not sure how he does it and suspect he’s going to blow a gasket at some point.

Some of us are have rooms in the Peninsula tower, he explains, some are in the Excelsior tower. I get my card, get to my room, down the water from my snack pack and bin the rest.

MONDAY 8.10AM

I feel better, kind of, as I catch the lift to the hotel’s breakfast floor. The choice of food is phenomenal, my appetite non-existent.

I’d expected to see others from the tour but see only pasty tourists in shorts and T-shirts, others in business suits, matched closely in number by hotel staff clearing plates and refilling food stations.

I serve myself noodles, sit at a table, lift the fork, retch, put the noodles down untouched. It’s not until I’m leaving that I see a sign for University of Melbourne staff and students, with an arrow pointing to another dining area. I go through, see Erdstein, Alix Bromley from External Relations, Gary McPherson’s Research Assistant Solange Glasser, James Hutchinson, Senior Lecturer in Clarinet David Griffiths, students.

“Have you eaten?” says Hutchinson.

“Yeah,” I say, sniffling. “All good.”

MONDAY 9.42AM

The first rehearsal of the Asian leg of the tour is at the durian-shaped Esplanade Concert Hall at 2pm, but Erdstein and I want to get footage of the freighted instruments being delivered to the venue, along with the lion’s share of Erdstein’s filming equipment. In theory, it’s a ten-minute walk from the hotel. In practice, it takes much longer.

The hoardings and security fencing for the Singapore Grand Prix a fortnight earlier are still in place, meaning we have to follow an unexpected loop to get to where we’re going, before finding ourselves facing five lanes of angry traffic without any pedestrian crossing.

“Should we make a run for it?” says Hutchinson, squinting through the sunlight.

“Yeah,” says Erdstein, mopping his brow.

I say nothing, just nod – even that’s an effort. We wait until the traffic settles, run for our lives, survive.

MONDAY 10.07AM

We’re in the loading dock of the Esplanade Concert Hall, next to a truck with double basses and university freight crates ready to be offloaded. Three unknown local men and two women in black T-shirts are waiting for direction and assistance.

“Are you Paul?” says one of the women.

“Yeah,” I say, sniffing, coughing.

“Paul. It’s Paul,” she says, pointing me out to the others.

“Hi,” I say, waving at everyone, looking at Erdstein. It’s not easy being this famous.

“We offload now?” says one of the men.

“Oh, I don’t know,” I say. “Maybe?”

“You’re Paul?” he says.

“Yeah,” I say.

“Paul Doyle?” he says.

“Nah,” I say. “I’m another Paul.”

Paul Doyle, the Faculty’s Production Coordinator, arrives looking like a man in charge, gives the delivery crew the instructions they’ve been waiting for. I follow Doyle and the procession of gear backstage, watch equipment being lifted, slid, carried.

Within minutes, Doyle, Orchestral Operations Coordinator Mandy Lo, and VCA Production student Geetanjali Mishra are out on the stage, checking seating arrangements, discussing and negotiating with the venue staff. I head backstage with Erdstein to find his gear, see a beautiful double-bass with a massive dint in its side.

“That’s not ideal,” says Doyle, coming through. “We’re going to need some gaffer tape.”

MONDAY 2.02PM

The orchestra is in place, in casual clothes, some bleary-eyed, waiting for Richard Davis to appear. I sit alone in the dress circle, listening to the vast swirl of noise as instruments – battling with the humidity – are fine-tuned and parts are played out of sequence. Concertmaster and PhD candidate Arna Morton stands, faces the troupe, tunes the orchestra.

Davis comes on stage in his black Nikes, smiles, shakes Morton’s hand.

The tour is Morton’s last outing as concertmaster. She was presented with a gift at the rehearsal before the Melbourne Recital Centre gig, and showered with praise by Davis.

“Arna has made my job an absolute dream,” he said at the time, addressing all of the musicians before turning to face Morton. “I couldn’t have done this job without you, and I wanted to convey my deep thanks.” And then, addressing everyone again, “The dedication that this young lady puts in, the passion, the stunning sound and intonation, her devotion … it’s truly remarkable.”

Today, Davis stands at the rostrum, smiles, says, “OK, welcome, everybody. Shall we do the Shostakovich?”

I sit watching, sniffling, not expecting much – maybe a slow, easy warm-up, but in the blink of an eye the concert hall goes from near silence to a barrage of overwhelming orchestral oomph. I remember lying on the grass as a child during an air display show with my dad, my body shaking as a Lancaster bomber flew low overhead, the almighty force of its engines nearly ripping my face off. It feels a bit like that.

Mezzo-soprano and soloist on the tour Heather Fletcher arrives on stage to perform Edward Elgar’s cycle of five songs, Sea Pictures, premiered by the famous English contralto Clara Butt in 1899. Each of the songs in the cycle is set to a poem that depicts the sea. It sounds amazing. And then it’s onto sections of Tide, by PhD candidate Alice Humphries, which is receiving its world-premiere on the tour while Humphries is in Perth with her family, in the late stages of pregnancy.

I get up on the stage, take some shots on my phone for Instagram, don’t want to get in the way. Falling through the harp strings would be bad, faceplanting the French horn inexcusable.

“If we do an encore it’s the Sibelius,” says Davis to the orchestra. “Or, if no-one claps we’re going home.”

MONDAY 6.50PM

Hutchinson, Erdstein, Haig Burnell – who will be sound recording the Singapore concert – and I are squished inside a taxi in a traffic jam in central Singapore. Our plan was to get to the Australian High Commissioner’s Residence before the students and other staff arrive – in Hutchinson’s case to troubleshoot, in Erdstein’s case, and mine, to film everyone’s arrival.

We’re not moving. I’m in the middle back seat between Hutchinson and Erdstein trying to hold in my sneezes, coughs and sniffles. I’m going to make them sick. I’m going to make everyone sick. I’m sweating profusely, trying to make small talk, feeling like death.

MONDAY 7.22PM

The Residence, designed by the recently-deceased Australian architect Kerry Hill, is swish, a natural flow from the many-windowed interior to the well-tended lawn, its steps strewn with thick white candles. Contemporary artwork lines the walls; there’s delicious food and – Australian, of course – wine.

“It’s a real honour to welcome you all here,” says the Australian High Commissioner Bruce Gosper. “I know it’s the Melbourne University Symphony Orchestra’s first overseas tour, and we feel very privileged that you’ve chosen to come here to share your superb music.”

He introduces Gary McPherson, who comes to the lectern, smiling.

“I just wanted to say to all the students in the orchestra that I was knocked out when I sat down and heard you playing in the rehearsal today,” he says. And then, to everyone, “We’re hoping this will be the first of continuing tours by our lead ensembles, particularly the orchestra. And that we’ll be returning to Singapore to play in the Esplanade Concert Hall again, which is really magnificent.”

The performance of the night comes from Conservatorium students the Invictus Quartet – Jin Tong Long, Rebecca Wang, Annika Cho and Nyssa Sanguansri – who play heart-lifting renditions of works by Joseph Haydn and Carlos Gardel.

MONDAY 9.45PM

The players are rowdy on the bus back to the hotel. For me, it’s the end of a very long day. For them, it seems, the start of what might be a very long night. I like the bonhomie, like that they’re happy, having a good time, feel miserable, feel like they’re a gang – and not a small one – I’m not part of. I can’t wait to get to bed.

TUESDAY 9.57AM

I’ve arranged to interview soloist Heather Fletcher to camera at 10am in Erdstein’s hotel room, which I realise, with some horror, is still some distance away. I’ve spent the early morning wandering about the city looking for gifts, not finding any, taking photos of public artwork, sneezing, coughing, dawdling.

I break into a run, pushing myself as quickly as I can through the humidity.

TUESDAY 10.07AM

I knock on Erdstein’s hotel door; he opens. His lights are set up, his cameras … but no Heather.

“Aren’t you meeting her in the lobby?” he says.

“Oh, shit, yeah,” I say.

The lift takes forever. When it arrives, Sean Marantelli, one of the flautists on tour, is inside. I want to interview him, yes, but now’s not the time to ask.

“I’m so sorry,” I say to Fletcher, who stands from one of the lobby chairs, smiling. I don’t want to shake her hand or kiss her cheek because I’m a germ factory and she has to look and sound her best.

“Oh, you’re very sweaty,” she says as we get out of the lift.

A PhD candidate at the Conservatorium and a voice lecturer in the Victorian College of the Arts Music Theatre program, she was invited to tour with the orchestra after winning the Conservatorium’s Concert-Aria Competition at the end of last year.

She sits on a chair by the window as Erdstein completes the finishing touches for filming.

“Sea Pictures,” she says, is “an incredible work”.

“It goes through different emotional journeys. The first piece is very much the sea. I am the sea, and I’m singing as the sea. The phrasing is very much around the language, and what an incredible phrasing it is. You juxtapose between dynamics and a pushing and pulling of the tempo in a way that Richard is so sensitive to and wants to honour. Elgar, despite setting these works by five different poets, links them beautifully musically by giving them these incredible themes that are repeated throughout.”

I wonder what the pitfalls of touring might be for Fletcher.

“As a singer, flying’s not great,” she says. “It’s very dry on planes and to accommodate that I wear something called a HumidiFlyer, which is just the most unattractive thing.”

I’m imagining the mask Bane wears in Batman – but the reality is less terrifying.

“It keeps the humidity in there, so it does the trick,” says Fletcher. “I usually have to explain to people why I’m putting on a contraption that makes it look there’s something wrong with me.”

The humidity troubles her far less than the hotel air conditioning and sealed windows, but she’s “old enough and experienced enough to know how to take care of that”.

As a case in point, she had to cut short her time at the High Commissioner’s Residence the previous evening. “I went for the beginning and very much showed my respects,” she says. “But I can’t vocally sustain conversations in a group of 150 people and then get up the next day and give my greatest performance.”

TUESDAY 10.47AM

Danna Yun, the orchestra’s pianist and celeste player, sits in the chair Fletcher had occupied in Erdstein’s hotel room. I’m perched on the bed, Dethridge is sitting on the floor near the wardrobe, her back against the wall. A Bachelor of Music (Composition) student, Yun also plays cello, as well as singing and playing guitar in her free time.

“There’s absolutely nothing that compares to playing in an orchestra,” she says. “Working towards a common goal with so many other passionate musicians just feels absolutely wonderful. I don’t know how to explain it. It’s like you’re creating a new world with all of these people you admire. We can only hope that the audience feels what we’re feeling when we play this music for them.”

Yun’s enthusiasm is infectious, her joy at being part of the tour self-evident.

“Oh yeah, I love it,” she says. “Being the pianist at the back, when I have like 7 million years of rest and then two notes, means I can really immerse myself in the sound world and enjoy how well everyone is playing. But it also means that when I do play there’s a bit of pressure. I have to make sure it’s perfect. And often, as is the case in rehearsals, it’s not really perfect.

“Because the piano and celeste are different in each concert space, it feels like I have to relearn the music all over again, within the two times I get to play during rehearsals – the touch, the tone, the shaping. You have to recalibrate yourself to suit the new acoustics as well as the new instruments.”

TUESDAY 1.45PM

There’s a 2pm dress rehearsal ahead of the concert this evening. Nothing will fall over if I’m not there on time but Erdstein and I are keen to capture as much as we can of the tour. Getting a taxi, I decide, is the only way. We jump in, the driver pulls out into the traffic.

“There’s that horrible road we had to run across,” says Erdstein ten minutes later.

“Yeah, I don’t fancy doing that again,” I say.

It’s nice to be out of the direct sunlight, feeling compassionate towards – and vastly superior to – the people I can see through the passenger-side window.

“Oh, look, there’s Richard,” says Erdstein.

He’s right – it’s Richard Davis, a bag, presumably with his concert attire, in hand, waiting at the side of the five-lane road in his black Nikes. This is my chance to save him from the treacherous crossing, to be the hero of the piece.

I roll down the taxi window, cough, shout, “Richard. Hey, Richard.”

He looks round, takes a while to triangulate the nasal whine calling his name, sees us, waves, comes across.

“Hey, would you like a lift? I say. “Jump in.”

He gets in next to Erdstein and thanks us, unaware – as we are – that we’re seconds away from being engulfed by a one-way system that will take us tantalisingly close to the Concert Hall without ever being able to pull over and let us out.

“I could have been there by now,” says Davis.

“Yes,” I say, laughing. Then, to the taxi driver, “Do you know how long we’ll be?”

The driver shrugs, points at the traffic.

“It’s the Stage Door,” I say. “Can you drop us there?”

He shrugs again. We’re making Davis late for his dress rehearsal, I’m still infectious and I might as well resign right there, right then, unless the taxi driver can reverse his way through the time-space continuum and get us to where we need to be in minus eight minutes.

The Stage Door, it transpires, is elusive. We get out of the taxi near a nondescript wall, trail after Davis as he negotiates an overgrown path that, sadly, leads nowhere.

“No, no, the other way,” he says.

There are some tardy students up ahead – I can see them, their instruments. We are saved. Saved! We follow them, Erdstein and I sweating buckets, Davis miraculously dry.

TUESDAY 2.22PM

I’m watching the rehearsal, having met with a local photographer to give him some direction, all the while snapping images on my phone for Instagram. The orchestra players, their hands full, stamp their feet as a means of applause at the end of beautiful solos, stop and start again at points of Davis’ choosing.

“I’d like you all to forget about the next concert in Shanghai,” he says. “This is the only concert that exists, so let’s all just keep all of our energy and focus on that.”

I sit, listen, watch, and it strikes me, for the first time, that what I’ve seen as an intimidating amorphous whole, an orchestral gang, in reality is more than 100 people, with more than 100 life stories, more than 100 pasts, presents and futures. Which makes it all the more remarkable when they do come together, repeatedly smashing it out of the park as a unified and unifying force of nature.

TUESDAY 6.30PM

Erdstein and I have split up temporarily. He’s taken his camera to the Gardens by the Bay to get some golden-hour scene-setting footage for our tour video. I’ve been roped in to assist the photographer with shots of the notables at the pre-concert alumni reception event, need to be back downstairs at 7pm to meet Erdstein for some backstage filming and potential interviews.

My cold, if anything, is getting worse. I check in with Alix Bromley, Damian Barber from Advancement, Peter Barron and Solange Glasser, who are welcoming the VIPs and administering their tickets, dash back upstairs to the fourth floor, spluttering, wash my hands in the bathroom, shake people’s hands in the reception, including that of a friendly Singaporean nonagenarian who graduated from the university in the 1940s.

“Let’s talk a bit about the Conservatorium of Music and how it fits with the University,” says McPherson from the lectern. “We are the largest and most comprehensive conservatory in Australia. We have about 1,200 full-time equivalent students, more than 800 students specialising in music, and we teach thousands of students across campus.

“But one of the problems we’ve had is a proper rehearsal space. For this tour the orchestra has rehearsed in a church hall and a number of small rooms in our Faculty of Fine Arts and Music. For a world-class orchestra, that’s not good enough.

“Our new building, which opens next year, The Ian Potter Southbank Centre, will have an orchestral space where we can rehearse a 120-piece orchestra. The students will be able to hear themselves and others across the ensemble in a way that will stretch them and allow them to really develop their skills.”

TUESDAY 7.09PM

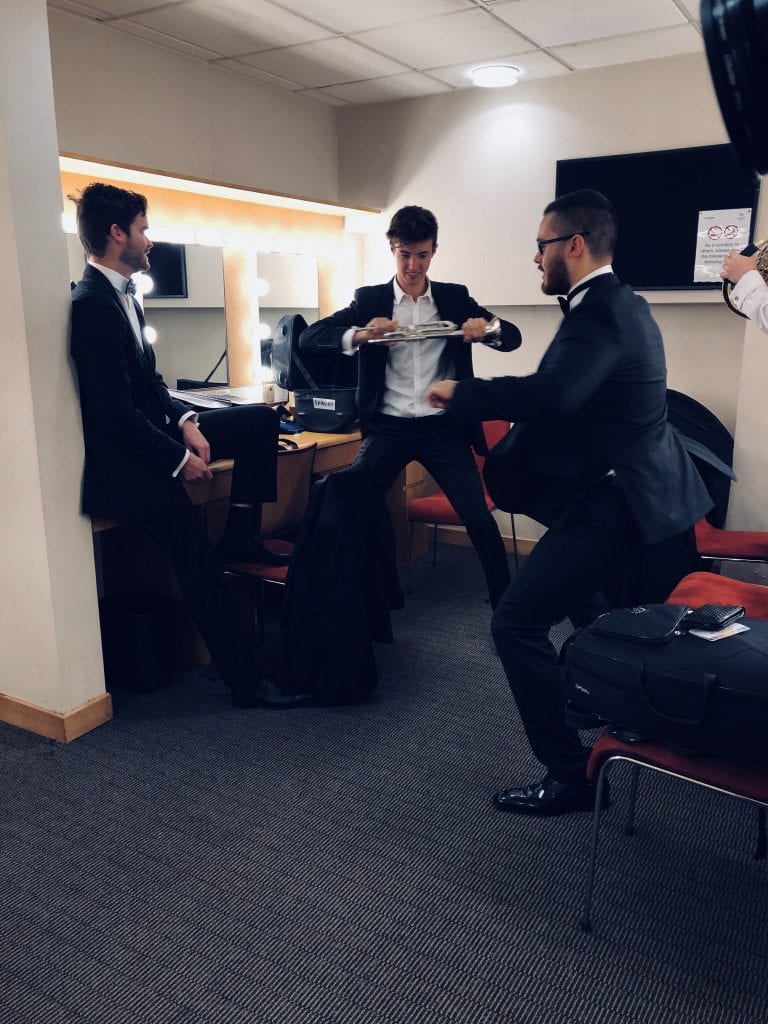

I give up on the lift and run back down four flights of stairs in an attempt to find Erdstein amid the buzz of pre-concert players getting ready.

There’s laughter, nerves, adrenaline galore. I duck in and out of shared dressing rooms, run back and forth along corridors I don’t understand, see Edwina Dethridge in black backstage attire. Edwina!

“Have you seen Greg?” I say.

“I have,” she says. “He’s in the green room.”

I find him – “I had to run all the way back from the Gardens,” he says. “Look at my shirt.” – follow him, watch him filming students in their shiny shoes, bow ties and concert dresses.

TUESDAY 7.31PM

Most of the orchestra is onstage and I’m in the stalls, sitting next to Joel Brennan, Head of Upper Brass at the Conservatorium. The hall is nearly full, the audience waiting, watching expectantly. I wonder if, and when, my sweat patches will coalesce into one big saline sea.

Arna Morton walks onstage in a black dress to applause, violin in hand, stands at the front of the orchestra, directs everyone to tune, sits. Davis, in tails and a white bow tie, walks in from the wings in shiny shoes, smiles, takes the audience applause, nods, shakes Morton’s hand, bows slightly, takes to the rostrum.

Having missed the Melbourne concert, my only exposure to the tour program has been in fits and starts, a blast here, a few bars there. To sit in one of the world’s best concert halls watching and listening to the program unfolding sequentially under the animated, fully-committed conducting of Davis is a revelation. Alice Humphries’ Tide is followed by Sea Pictures with Heather Fletcher. She delivers an incredible performance while the orchestra plays out of its skin.

After the intermission it’s Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D Minor, Op.47, an exhilarating rendition that receives thunderous applause, and then the Sibelius encore, Valse Triste, Op. 44, No.1, before a second encore in the shape of Elgar’s Wild Bears – two minutes of high octane mastery. Many members of the audience get to their feet, the players look happy, it’s been a tremendous success.

“That’s the best they’ve ever played,” says Brennan who, to my left, is applauding loudly.

WEDNESDAY 4.48AM

I’m sitting on the tour bus with stinging eyes watching students file past a sex shop window and a cardboard cut-out of a Singaporean policeman with a speech bubble that says NO STEALING!

Hutchinson, still smiling, has administered the morning snack packs. I can’t believe everyone’s good mood. Erdstein stares at his phone, I stare at mine. The bus leaves for the airport at 5.05am.

WEDNESDAY 7.12AM

We’re back at Changi Airport, ahead of the flight to Shanghai. I wave at familiar faces in the Duty Free shops, feel completely blocked up, unhappy with my lot in life. I could buy gifts for my kids – they’d like that – but the truth is I can’t face it, not today.

I check my ticket for the boarding gate number, walk slowly in what seems to be the general direction, see a small group of students standing and sitting. Three of them are playing their trumpets with practice mutes next to a travellator.

One of those, Mads Sørensen, is in the first cohort of the Conservatorium’s Master of Music (Orchestral Performance), in which he – like others on the course – is paired with a professional mentor from the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra.

Playing at the airport, he says, is par for the course. “We need to keep in shape, especially with a program like this where we have a lot to do,” he says. “We need to make sure our technique is there, and if that means practising in the airport, that’s what we do. I always try to make the most of those times when I travel.”

WEDNESDAY 7.45AM

We’ve been through one gate, have to wait again for the boarding call. I find myself sitting next to Natasha Fearnside, a clarinetist enrolled in the Conservatorium’s Master of Music (Music Performance).

She completed her Bachelor of Music in Queensland nearly a decade ago, and, after her final recital, decided she just needed a break – “which ended up lasting eight years,” she says, laughing.

In the interim, she’s taught clarinet at high schools and taken lessons with the Conservatorium’s former clarinet teacher Robert Schubert.

“It’s been nice to actually talk to the rest of the musicians on this tour,” she says. “Normally, I don’t really socialise beyond the minimum because everyone’s about 100 years younger than me.”

The concert at the Esplanade Concert Hall had its difficulties, she says.

“I actually felt very far away from the strings. My clarinet supervisor David Griffiths was there, and he told us we sounded like we were behind in the rehearsal. That meant we had to play in front of the beat slightly just to sound like we’re in time. It made me feel like I was too far ahead, even though it came across like we were playing together.”

WEDNESDAY 8.30AM

I’m sitting between two of the players on the plane. On my left is Ian Crossfield, a double bassist who started playing the cello at age 11 but, when given the choice by his father, chose the biggest instrument possible.

“I always wanted to do music,” he says. ‘With the double bass, what I had in mind was the band The Living End. I pictured myself standing on the bass doing spins, and that just slowly developed more and more into a love for classical music.”

He’s in his Honours year at the Conservatorium and is considering auditioning for the Master of Music (Orchestral Performance) next year. In the meantime, his focus is on the current repertoire.

“It’s a funny program for the double bass players,” he says. “In the first half we don’t really get started, because there’s a lot of vibrato that makes our parts spaced quite far apart. And then, in the second half, for the Shosta, we do a lot of fanging.”

Sitting to my right is Tom D’Ath, a clarinetist in his Honours year in the Bachelor or Music. We spend a long time chatting about reeds, about their density, what happens when you attach them to the mouthpiece, their many, seemingly infinite, pros and cons.

“I’m playing a different instrument for each of the pieces on this tour,” he says. “In the Alice Humphries, I’m playing B-flat, in the Elgar I’m playing A clarinet, and then E-flat for the Shostakovich. I’ve also got a few fairly exposed solos – eight bars or so – which means everyone will know if it’s not working right.”

Like everyone, he attended 20 hours of full-orchestra rehearsal for the tour, on top of his standard four hours of solo practice a day which, for now, has fallen by the wayside.

“It’s just a different mode of being performance-ready without really touching the instrument that much,” he says. “That’s tricky. For the ensemble, last night was probably the most cohesive performance we’ve had, but from a personal perspective, I knew I made a range of errors. Maybe they were avoidable, maybe they weren’t.

“At home I would have spent an hour warming up, so it’s about balancing your expectations with the reality of the situation that you’re in. I just have to try and move on.”

As opposed to beating himself up?

“Yeah,” he says. “When I make a mistake generally I think it’s massive – a giant, obvious spot in my playing that sounded awful. But then, that’s what I’m hearing on the stage, which then has to go past all the strings, before travelling another 25 metres out to hit an audience member. Everything amalgamates to an extent, so it isn’t nearly as noticeable as I think it is.”

A member of the cabin crew offers us water or orange juice. D’Ath opts for orange juice; I opt for water to wash down my Singaporean pseudoephedrine mixture.

Our chat may be over, I think. It’s maybe time to fire up the in-flight entertainment, get some shut-eye.

“On the other hand, I want to be that critical,” says D’Ath. “I want the performance to be the best thing it can be. Am I blending with the flutes? Am I blending with the clarinets? The big one is the piccolo – am I able to blend with that? Nobody gets hurt if you make a wrong note or your intonation isn’t great, but in the profession it can be the difference between getting hired or not.”

I nod, stop my recorder, start watching the HBO show Succession, try to stretch my legs under the seat in front of me, to let my mind drift …

Which it does, before returning to the orchestra, the tour. It strikes me that in the normal course of events we arrive and leave, showing what we want to show of ourselves and hiding everything else, but on tour it’s different: there are the late nights and early mornings, the bumping into each other in corridors and 7/11s, the airports, the yawning, the dawning.

Nearly everyone is missing friends and family, making the experience ripe for new friendships, and new – if only temporary – family.

WEDNESDAY 3.58PM

Edwina Dethridge has her hand in the air. We follow her through Shanghai’s Pudong International Airport, out into the smoggy air, towards the three buses that have been booked to take us to the Hengshan Picardie Hotel in the city’s French Concession. The mood is subdued – read exhausted – on the one-hour journey.

We pass construction sites with bamboo scaffolding, people texting while riding their motorbikes along the freeway, an uncountable number of billowing Chinese national flags. We arrive, get more footage, wait in the lobby for what feels like a year as passports are handed over in return for room keys by the hotel staff.

“So, this is your free time now,” says Dethridge, addressing everyone. “Have fun tonight. Remember to stay in groups and let others know where you’re going. There’s a buffet here at the hotel at 6pm.”

WEDNESDAY 5.57PM

Dethridge is sitting in the lobby next to a table overflowing with passports. She’s agreed to be interviewed with the proviso that she may be interrupted – which she is, constantly.

How is she enjoying the tour so far?

“It’s a bit of everything,” she says. “It’s been exciting, and really fun, very rewarding. I’m not going to say very stressful because—”

A string player stands in front of us, wants her passport. I pause the recording, smile, wait till she leaves.

“Maybe at times it’s been stressful,” says Dethridge. “Which we knew it was going to be, considering the size and scale of what we’re trying to achieve. It’s also been a bit surreal. I’ve done regional theatre tours involving about nine actors in a group touring around Victoria, but—”

“Can I have my buffet coupon?” says one of the players, butting in.

“Yeah, they’re just here, in this pile,” says Dethridge, pointing.

“Oh, yeah,” says the player. “But …”

I pause the recorder, unpause.

“I’ve done one Asian audition tour before but that was just three staff members for four days,” says Dethridge. “To look after more than 100 musicians in a foreign airport that I’ve never been to before with three buses that are miles way is a whole other ball game. But just being able to pull on all my experiences from previous jobs has really helped. I think that—”

Someone interrupts, isn’t happy with their room allocation – the carpet, he says, smells odd.

“Okay, sorry, Paul, just give me a second,” says Dethridge.

I pause, smile, wish everyone would leave Dethridge alone for five minutes, unpause, point out the obvious: that, as well as the students, Dethridge and Hutchinson have been looking after all of the staff.

“But vice versa as well,” she says. “It’s like one big spiderweb, really, and we’re all sort of joined together in different corners of the—”

“Do you know where Ting is?” says a young woman.

She means Wang Zheng-Ting, a graduate of the Shanghai Music Conservatory who completed a PhD in Ethnomusicology at the University of Melbourne. A Mandarin speaker, he’s the tour translator.

“Actually, I think he’s just through there,” says Dethridge, pointing to the dining area.

“Oh, yeah, right,” says the young woman. “Because I just need some help with this.” She opens a map, shows it to Dethridge.

Pause. Unpause.

“To be honest, I just want to sleep,” says Dethridge, facing me. “I’ve had about three hours sleep the last two nights – which is fine. If I have even a moment to breathe I’ve got to just look ahead at that evening or the next day and what I need to do.

“Student welfare has become a big part of my job. Dietary requirements are an important consideration and I had a chat to some of the asthmatics on the plane today because the air quality in Shanghai can just go up and down. Tomorrow, I’m hoping for a long lie. I really need—”

“Sorry to interrupt,” says one of the brass players. “Do you know where dinner’s being served?”

THURSDAY 9.30AM

Dethridge, I’m told at breakfast, was woken at 5am to take a student to hospital with suspected food poisoning. Much of Erdstein’s equipment, meanwhile, won’t clear customs until tomorrow lunchtime. Not a problem, other than the fact we’ve arranged to interview Richard Davis to camera in Erdstein’s hotel room in 30 minutes.

“Can you just hold this steady?” says Erdstein in his room, ten minutes later. In lieu of his tripod, one of his cameras is propped precariously on top of a table lamp, a cardboard flyer tucked under the lamp’s base for balance. His light deflector is wedged into the luggage stand. Erdstein is crouching behind a pile of hotel pillows with his second camera. I’m the stand-in for Davis, until he arrives.

“Just say something, so I can check the sound,” says Erdstein.

I talk about my morning so far and realise, for the first time on the tour, my nose isn’t blocked and I don’t want to collapse in tears. As far as I know, I’ve made no-one sick, and it seems possible that I’ll even start to have fun.

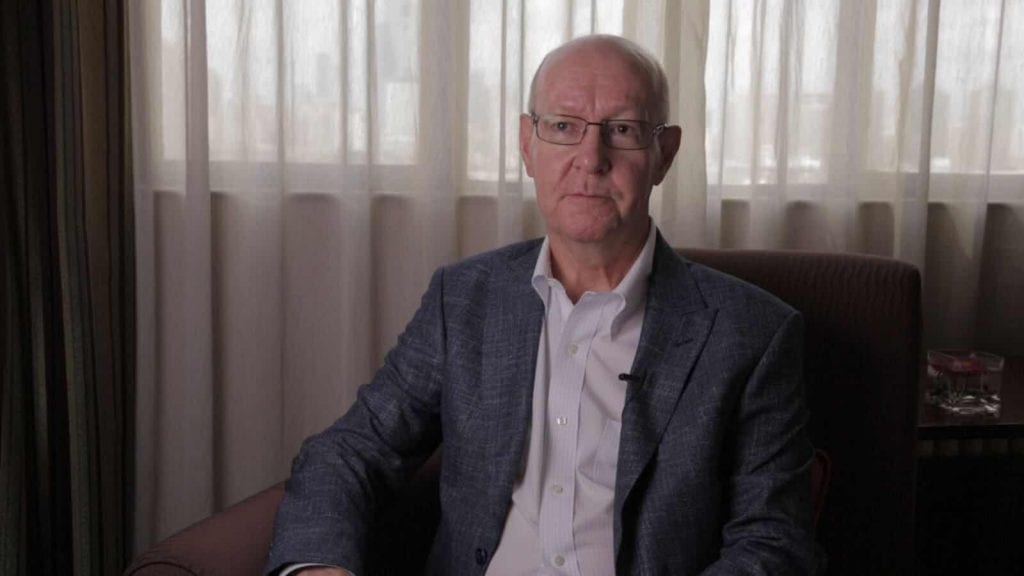

THURSDAY 10.01AM

Davis knocks at the door, comes in, squeezes past the assembled equipment.

“Oh, this is very … um …” he says.

“Yeah, I know,” I say from the end of Erdstein’s bed, explaining the situation with the gear. “If you could just sit there …”

While Erdstein is adjusting the camera, I tell Davis how highly he’s held in regard by the players, how much they’ve fallen over themselves to express their admiration and gratitude for his skill and temperament as a conductor – and not just on tour but since he joined the Conservatorium from England last year.

“Well, you’ve got to remember I was playing flute in professional orchestras for 30 years before becoming a conductor,” he says. “I learned very early on that the conductors I loved and wanted to play my best for were the ones that encouraged me.

“If you encourage people, if you give them images, if you give them just a smile, they will play better. And it is just so lovely to see students playing better than they’ve probably ever thought they could. I feel that way every time I conduct this orchestra, and so, yes, I’m always on the encouraging side.”

Even when he’s not having a bar of it? “When people cross a line, or when they make too many mistakes, too often, you just need to give them a look,” he says. “But sometimes that’s enough. You don’t need to stop the orchestra. You don’t need to make them feel embarrassed.”

The prospect of taking the orchestra on its first international tour – as well as the forthcoming relocation to The Ian Potter Southbank Centre – was a motivating factor for his joining the Conservatorium. On arrival in Melbourne, he wrote a letter to each of the orchestral students outlining his expectations.

“I told them, I will treat you like a professional, but you have to do something in return,” he says. “You have to listen to the music, to recordings, actually three recordings, to get different tempi. And you have to practise your part. I didn’t want to be one of those conductors who was just a note-basher, where the first few rehearsals are about learning the music.

“Now, on tour, they’re learning how to balance fatigue and jet-lag with still going onto the concert platform and playing like angels, and that’s part of being a professional musician.”

I’m curious to know what he actually does up there on the rostrum. One of the players told me the faces Davis pulls during performances can be hilarious.

“Well, the role of conductor is often misunderstood,” he says. “Are we just waving our arms? Are we just having fun? And, yes, some of it is actually that. But I have to look at a piece of music. I have to look at the orchestra I’m working with. And I have to immediately think, what can I get? Can I get my interpretation 100%? Can I do a lot of rubato, which means you rob time, you take time, you actually pull on the heartstrings of the audience.

“My preparation begins weeks and weeks before the first rehearsal. I have to know exactly the articulation, the speed. If there’s any doubt in my body at the first rehearsal it will confuse the players. I’m not dictatorial but I have to be absolutely firm in my ideas.”

Davis is very eloquent and generous when discussing the benefits of touring to everyone else – but what’s in it for him?

“Oh, I have to think about that,” he says, looking at the floor. “What do I get out of it?”

I sniff, nod at Erdstein – peekaboo! – behind the pillows.

“Touring is a very special thing for a conductor,” says Davis eventually. “By repeating performances, you’re going to get closer to your ultimate interpretation. And I think, if I get 85%, 90%, which is what I usually get because there are always some compromises, I’m a happy man. But actually, in Singapore the other day, it was about 98%. So I am going for 100% tomorrow in Shanghai.”

I thank him as he leaves the room, wait until he’s out of sight, run down the corridor, jump in the lift, see Sean Marantelli the flautist again – Hi Sean! – belt down to the lobby to get Gary McPherson for his interview to camera.

“Yeah, good to go,” says Erdstein after attaching a lapel mic to McPherson’s snazzy suit jacket – “I got it for 80 bucks in Azerbaijan six weeks ago” – and checking the sound levels. I sit on Erdstein’s bed, next to his main camera. McPherson seems happy, gregarious – as well he should. He was at a jazz club in the Bund the previous evening – “My god, the singers were spectacular” – and, more importantly, the tour is going well.

“This is going to be something the musicians will remember for the rest of their lives,” he says. “For many, including those who won’t go on to be professional performers, it’ll be the lifeblood of their love of music well into the future.”

Does he feel the stars have aligned for the Conservatorium?

“I do,” he says. “And at a really critical point in our history. I can’t think of any conservatory in the world that’s so close to the city and so well-connected with all the other major arts organisations.

“When we move to the Southbank campus early next year, we’ll be able to better connect with all the other disciplines in our faculty, from television, theatre, visual arts, music theatre. It’s a very special time for us.”

THURSDAY 4.30PM

We’re on a bus again, en route to the day’s official engagement – an evening boat cruise along the Huangpu River, hosted by the Shanghai Conservatory of Music.

By chance, I’m sitting next to James Hutchinson, who – despite the hotel ATM having swallowed his credit card, and averaging, he reckons, only four hours sleep a night since the tour began – is still in a chipper mood.

He’s missing his son, I’m missing my two boys, though neither of us have had much downtime to dwell on the fact.

“That sucks about your card,” I say, double-checking my phone wallet instinctually for mine, realising in the same instant that I have no memory of retrieving it from the machine that ate Hutchinson’s the previous evening.

“Oh, shit,” I say. “I think I’ve lost my card too.”

“We can sort it out tomorrow,” says Hutchinson, unconcerned. “Apparently, they get taken to a bank just down the road. Ting can come with us to translate.”

How much work has the tour been for Hutchinson?

“It’s difficult to quantify exactly,” he says. “We started discussions with the Singapore concert venue around two years ago. There were a lot of big pieces of the jigsaw to get in place, such as the flights for 101 students and 20 to 30 staff, a similar deal for the hotels, and for all the buses to transport people around.

“But even once you’ve got all those big things organised, the level of detail then just continues until you get down to the finer and finer points. So, yeah, it’s been a two-year project, and it’s just really exciting to see that come to fruition.”

An amazing effort on his part, I say.

“Oh, thanks,” he says. “I think the way that Richard approaches his conducting and his management of the orchestra is the same way we approach the administration side. We treat the players like professional musicians, and make sure we look after them. I think they respond really positively to that.”

THURSDAY 6.30PM

The Huangpu River is ablaze with reflected light from the panoply of neon and LED-clad buildings on the shore. I’m on the deck of the cruise boat with Erdstein, capturing some footage.

We go downstairs, join the line of students and staff queuing up for their turn at the buffet, see Danna Yun and horn player Rosemarry Yang discussing the tour with a reporter from Shanghai’s Kankan TV Station.

We sit, hear the clinking of a glass, see Faculty Dean Barry Conyngham getting up to make a small speech to the students.

“As soon as I’m finished making a few comments and thank-yous, the boat will start moving and it will be time to go upstairs and enjoy the spectacular views,” he says. “But it’s very important for me to say that this evening wouldn’t have happened without the fantastic help we had from our colleagues at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music.

“President Lin Zaiyong and I have known each other for some years now, and I just want to say thank you, personally, for your fantastic organisation and friendship.

“Let me also say, we will get a chance to welcome President Lin and many of his students and colleagues to Melbourne next year, when they come with a new production of an opera that’ll be one of the first events in The Ian Potter Southbank Centre.”

THURSDAY 7.36PM

We’re on the deck watching and listening to a fanfare by the Conservatorium’s Brass Quintet, the Bund gliding slowly by on the shore. The applause rings out as they finish, as do cheers. Spirits are high, energy levels good.

The full moon makes little impact against the neon grandeur of our surrounds.

We gather for a performance of two Chinese pieces – Spring Wind and Purple Bamboo Melody – by the Conservatorium Octet, alongside a couple of Percy Grainger works, and a performance by a saxophone quartet from the Shanghai Conservatory of Music.

And then there’s Ting, our tour translator, who plays what he’s described as a mouth organ but which looks like a steampunk machine gun. It’s incredible sounding – part accordion, part I don’t even know.

I sit on a deck chair with Cecilia Dowling, a viola player who has been dividing her time between working at the University in Alumni Relations and completing a Master of Music (Music Performance) at the Conservatorium.

“I’ve just come back to playing classical in the last few years,” she says. “I did an undergraduate in arts and a diploma in creative arts, painting and drawing, then Honours in literature. And then I decided that I was jealous of the students I saw running around campus with their instruments on their backs.

“I auditioned at the Conservatorium, and they suggested that I do the masters but at that point I couldn’t because I didn’t have an undergrad in music. I did a year and a half of the Graduate Diploma in Music, which was great because I needed to get back into the mindset.”

Will she stick with performance once she’s done?

“Yeah, definitely,” she says. “I’ve got a few different ideas up my sleeve. But it’s good to be able to have a money-earning job while studying and returning to feeling fully confident. Sometimes it’s not easy, even when you’re a really great classical musician, to make consistent money. Quite a few people do manage it, but it’s a big task, so I’m glad I’ve got my salary.”

FRIDAY 10.28AM

It’s concert day in Shanghai and, because his gear still hasn’t cleared customs, I’m in Erdstein’s room again, helping him set up a makeshift studio for concertmaster Arna Morton, who I can only imagine is feeling sad given it’s her last hoorah with this orchestra.

She arrives, has the same WTF reaction Davis and McPherson had on seeing the set-up, sits by the window, blinking into the harsh studio light.

“So, yeah, after four years, this evening is my last as concertmaster of the University of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra,” she says. “It feels like the end of an era. I definitely know I’m going to be quite emotional after the performance.

“What I’m going to miss most is working with Richard. He’s been a huge mentor for me in my development as an orchestral musician and he really believes in my ability, which I don’t always, so it’s nice to have someone of such an amazing standard think that I can make it.”

What exactly does their professional relationship entail?

“Richard’s role is really to invoke the feeling behind the music, and absolutely to give an indication of time,” she says. “But it’s a lot easier to follow a musician actually playing the music. My role is to interpret what Richard’s doing and then show that practically in my playing, for the other section leaders to follow. Then it’s up to the other players in those sections to follow their leader.

“It’s like a little business, where you’ve got a CEO, and then managers, and everyone is reporting to someone above them. That’s how everything stays in time and together.”

Being able to repeat the same program on tour, she says, has paid dividends.

“This is the first program we’ve actually done multiple times,” she says. “In my time at Melbourne Uni, most concerts have only been performed once at the end of a couple of weeks of rehearsals, and this is the first time we’ve performed the same program more than twice. I certainly felt a real rise in the quality of the playing and the attentiveness of the musicians in Singapore.”

On the downside, the onstage-offstage balance of touring has been tricky.

“It can be quite exhausting,” she says. “In Singapore, we were out sight-seeing the day before the concert, and then, on the day itself, I just felt a bit overwhelmed – dealing with coming down from a big performance, travel, all of that. But thankfully, I was able to sort myself out. I just took some time in my room and regained my composure and focus. And then, in the end, we played even better than in Melbourne.

“Everyone was really attentive, and when we started to realise we were producing such professional results, it kept everyone onboard. We got to the end and I just thought, ‘Wow, how did we do that? Amazing’.”

FRIDAY 1.32PM

I’m not that fussed about retrieving my bank card but I’ve committed. Hutchinson and I follow Ting through a public park, down streets, back up the same streets, down others, stopping while he confers with people in words we don’t understand in search of accurate directions.

“He says it’s this way,” says Ting, returning to us.

“Isn’t that the opposite direction to what that other woman told us?” says Hutchinson.

“The guy from the hotel pointed that way,” I say, nodding in yet another direction.

FRIDAY 2.24PM

We have our bank cards, thanks almost exclusively to Ting. Hutchinson’s role and mine has involved looking like the people in our passport photographs and trying not to seem too stressed about the fact the bus for the Shanghai Symphony Hall is leaving at 2.30pm.

Ting’s role has involved getting us past the 16 people with numbered tickets waiting forlornly for assistance, before impressing upon the cashier that we are upstanding citizens and professionals of the highest order, then knocking repeatedly on the cashier’s window to ask her politely to get a move on.

And now, with our cards back, we’re running – nearly. It’s more like a competitive walking event. Our kneecaps are trying to keep up with the pace we’re setting through the park, up the avenue, over the road crossing, towards the hotel.

FRIDAY 3.00PM

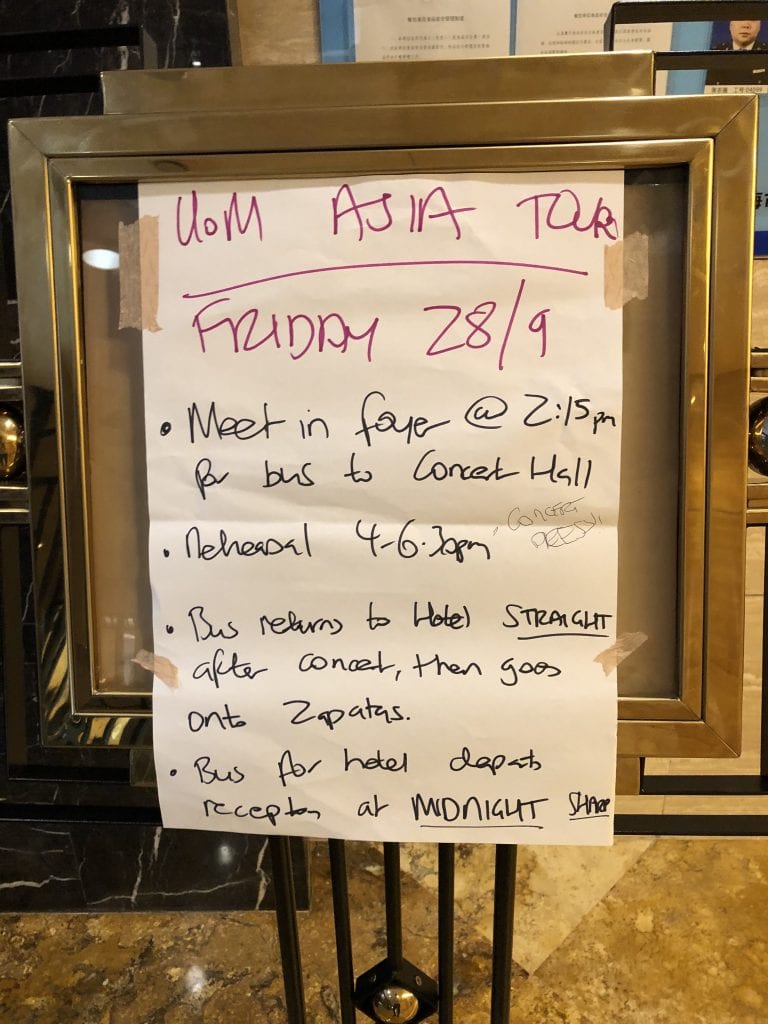

The players file off the bus, down an exterior concrete stairway and into the backstage area of the Shanghai Symphony Hall for the dress rehearsal, their first contact with the space.

Ties are tied, dresses fixed up, instruments tuned and played as the musicians walk back and forth outside their changing rooms, then through to the empty concert hall to take their seats.

“So, welcome back, everybody,” says Davis when he arrives onstage. “We have a bit of a problem today … How do we make ourselves sound even better than we did in Singapore?”

By way of an answer, the orchestra plays incredibly, stopping and starting on Davis’ command.

FRIDAY 5.05PM

Davis calls the rehearsal to a halt, announces that there’s a very special guest in the house. University of Melbourne Chancellor Allan Myers climbs onto the stage, stands at the rostrum.

“You should all be very proud of the way you realise the aspirations of the University of Melbourne,” he says. “There’s a palpable sense of excitement for this evening’s concert. I think they say ‘break a leg’ in the theatre. I don’t know what they say for orchestras, but I wish you all the very best of luck.”

FRIDAY 5.45PM

I’m leading Erdstein and a local photographer through what I hope are the right corridors of the Shanghai Symphony Concert Hall to reach the alumni reception at which Conyngham, McPherson, Myers and Davis will speak, alongside the Australian Ambassador to China, Her Excellency Ms Jan Adams.

Dozens of recent and not-so-recent alumni gather round for the official speeches.

“The University of Melbourne has produced a large number of great Australians, as I’m sure you know,” says Adams. “Leaders like former Prime Minister Julia Gillard, celebrities like Cate Blanchett. And Nobel Peace Prize winners like Peter Doherty in Immunology and Elizabeth Blackburn in Biology. But the university also has a great orchestra, and really I congratulate the people who’ve been involved in putting together what must be an enormous undertaking to bring more than 100 musicians here tonight.”

There’s applause. Conyngham takes to the lectern, thanks Adams, says, “One of the things that’s often said at graduation is that once you have your degree from a university, it lasts forever. You are forever alumni of your university. And many, if not all, of you here are forever members of the community of the University of Melbourne. And you will be welcomed warmly and enthusiastically any time you come back.”

FRIDAY 7.25PM

I’ve decided to watch the evening’s concert from the wings with Erdstein, which allows us to film the players going onstage and soak up the frenzied excitement at this, the tour’s culmination.

The laughter and jokes as the players approach the stage door dissipate, replaced by the decorum audiences might expect of classical musicians. Chairs fill on stage, the orchestra is back together. Heather Fletcher stands backstage doing vocal warm-ups, flanked by Davis and Morton, who are waiting for their turn to go out.

Dethridge, Doyle, Lo and Mishra are on hand, as they have been all tour, to work with the venue’s stage manager, to make sure everyone arrives on time, to deal with problems no one has, or could, anticipate.

I’ve wanted to interview Doyle for days, hope that this evening will be the right time.

“Yeah, but not during the Humphries piece,” he says. “It’s only seven minutes long, and then I need to go on and rearrange the seating.”

Erdstein and I can see the stage and audience through a glass portal on the stage door. Seats are filling quickly, ticket sales have been good. And then, it’s Morton going on stage – applause – and then Davis – applause.

They launch into Tide and, from the outset, I can see through the portal that the audience is rapt. Apart from one or two people who are conspicuously reading something on their phones.

One woman’s face suddenly lights up, a green laser aimed at it from somewhere in the auditorium. She looks up, tries to locate the source, puts her phone away. The same trick is repeated – I don’t know by who – with a man sitting three rows back from her. One minute he’s smiling at his phone screen, the next he’s been harried by green laser light in his eyes.

He puts his phone away, looks slightly mortified – it’s clearly an effective technique.

FRIDAY 8.30PM

A special pre-intermission treat has been prepared in the shape of Good News from Beijing, an orchestral piece by Zheng Lu and Ma Hongye. Sadly, the local stage manager has brought up the house lights in the small interval between Davis leaving the stage and returning to the rostrum. People get up, start to leave the hall. Everyone backstage is in a flap, apart from Davis, who says, “Don’t worry, they’ll come back, wait and see.”

He strides back onto the stage – and he’s right. People stop mid-flight, realise what’s happening, return to their seats.

FRIDAY 8.58PM

I get a chance to chat with Paul Doyle during Shostakovich.

“My job on this tour has essentially been to think ahead of what’s happening and to try and provide people with a solution they need before they realise they have a problem,” he says.

He’s been with the Conservatorium for almost five years. His biggest tour prior to this one was with the West Australian Symphony Orchestra in 2006, a two-week, five-city operation.

“This tour’s been really fun,” he says. “It’s been good to be a part of such a rewarding experience for the students and, hopefully, the audiences as well. I feel tremendously proud to have anything at all to do with these excellent musicians. I feel really positive about the next generation of Australian orchestral musicians and soloists, because the standard of people that I’m working with on this trip has been so high.

“They’ve had a bonding experience that I think is going to have some really interesting outcomes for the cultural life of our country in years to come.”

He’s quick to praise the efforts of all the tour staff, not least VCA Production student Geetanjali Mishra, who’s spent much of the week running from narrowly-averted crisis to near-catastrophe, and is still running – literally – when I catch her for a minute in the corridor.

What else has she learned?

“Oh, I’ve not had a chance to think about that,” she says. “I haven’t really had the time. I’ll do a debrief and self-reflection after the tour, and that’s when I’ll be able to sit down and actually think about what I did.”

FRIDAY 9.30PM

The main concert program finishes with a standing ovation and hugely animated audience, not a laser beam in sight. Davis turns, faces the audience, acknowledges the players, walks off stage, only as far as the stage door, turns, returns to the rostrum for the Sibelius encore.

That too is met with rapturous applause. He repeats the procedure, walks offstage, takes a sip of water from the bottle Dethridge has waiting for him, heads back out for a barnstorming rendition of Elgar’s Wild Bears.

Again, huge applause – the audience is loving it. Again, Davis bows, walks back out through the stage door to the backstage area, sweating, smiling, and says, “Oh, I think that’s enough for now …”

Then he turns, heads back out, and leads the orchestra through an even more ferocious version of Wild Bears. It feels like the roof might come off the concert hall.

People are still on their feet clapping and cheering as the players start to file backstage. Happy faces, smiles, hugs.

“That was amazing,” says flautist Lauren Gorman, who has been performing with the orchestra since 2012. “Everyone played so well tonight. It felt terrific – a really special concert. I think, at first, there was a few people in the audience shuffling and eating chips or something, and I was like, ‘Okay, that’s how it’s going to be’. But by the end we had them in the palm of our hands. And I mean, we owe some of that to Shostakovich … that’s the least that we owe to Shostakovich.”

Was she happy with her own performance?

“Oh, I felt like I played really well,” she says. “The whole orchestra was kind of looking up and smiling, and taking risks here and there. And it’s those little risks that really make a performance quite magical. Because you’re not just playing in that safe zone. So, yeah, personally, I felt really, really great. It’s something I’ll remember forever. I think tonight’s performance was by far the highlight of all three.”

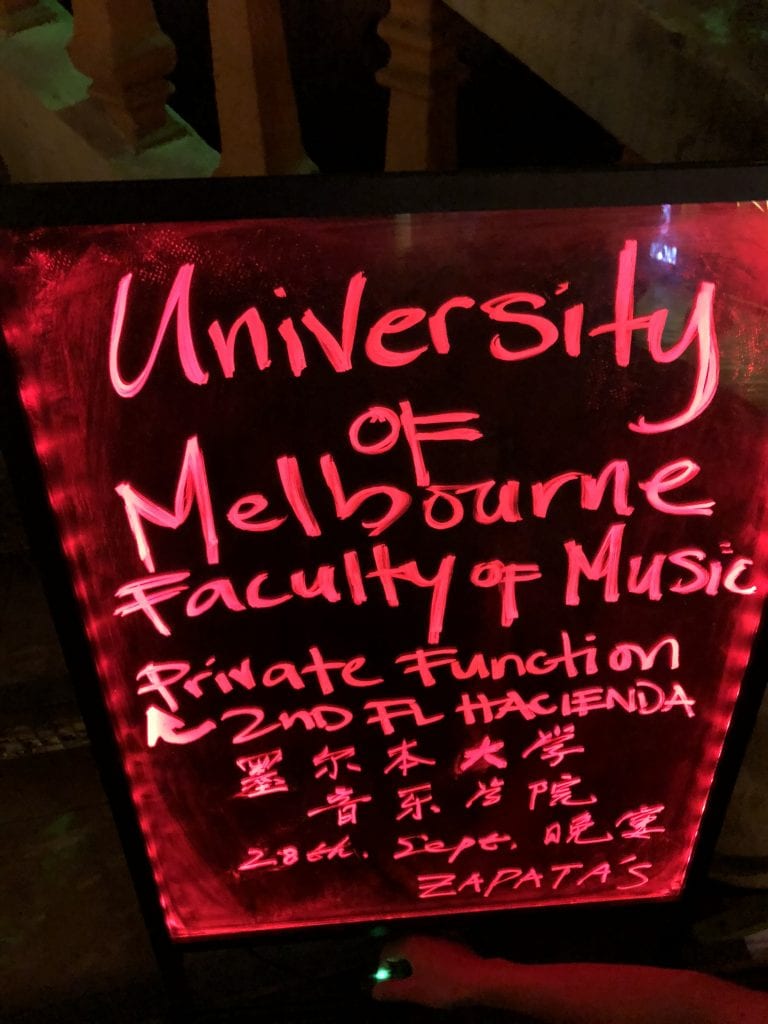

FRIDAY 10.26PM

It’s a short walk to Zapata’s, the Mexican-themed nightclub that’s been booked for the end of tour get-together. I’ve been expecting a subdued affair, people comparing their performances in some kind of studious way. But it’s party time. There’s dancing, cheering, singing.

For my own part, I’m glad to have got through it all, happy my cold has gone without killing anyone. It’s time to cut loose.

Students cheer Gary McPherson onto the dancefloor, Davis is there too, throwing shapes, as is Conyngham.

A conga line starts up and I’m swept into it. Erdstein – for once not holding his camera – dodges the bullet, backs deftly into the shadows.

SATURDAY 2.03AM

Paul Doyle grabs me on the dancefloor, lifts me off my feet, tells me I should interview the principal oboist Brienne Gawler. Amazingly, despite the late hour, she’s up for it, and we go downstairs to the outside bar.

Unfortunately, given the festivities, I don’t feel my usual journalistic rigour. Instead, I’m lobbing questions at her like a tennis player at the end of a six-hour five-set stunner. Are you happy? Do you like touring? Luckily, she’s an eloquent interviewee.

“I’m continuing with my studies next year but there are many of my colleagues here tonight who are leaving,” she says. “That definitely comes with a bit of emotion.”

I hold the phone mic up as close as I can because I know what it’s like trying to transcribe audio that’s been done in noisy pubs with music – in this case Living La Vida Loca. You go through, stopping and starting, each bar of the song taking the best part of a decade in emotional terms to transcribe. Luckily, I pay for a transcription service these days. But I’ve been there, in the trenches, so I hold it close to Gawler all the same.

“What I love about our orchestra is that everyone is so supportive and encouraging of each other,” she says. “That’s a really special quality. We’re all in it together. This tour has really united us. We’re all here to perform music, we’re all here with one purpose, one goal, one mission. I think that’s what brings us together.”

When I next see Gary McPherson at the edge of the dancefloor, the party’s still going strong. He tells me his suit will need to be dry-cleaned – for many, the advanced motor skills required to master an orchestral instrument have buckled under the intense pressure of Taylor Swift.

“They’ve done you proud,” I say to McPherson, nodding at the dancefloor.

He pulls me closer, says “Nah mate. Just look at them all.”

I look at them all. Staff. Students. People are laughing, dancing, their arms aloft, brimming with relief and self-belief.

“They’ve done themselves proud,” says McPherson. “They really have.”

- Learn more about The Ian Potter Southbank Centre, a new home for the Melbourne Conservatorium.

- Find out more about the Conservatorium’s Master of Music (Orchestral Performance).

The University of Melbourne would like to thank all who donated to the Orchestra Touring Fund and the families and friends of the following trusts whose vision helped make the 2018 Asia Tour a reality:

The Sidney Myer Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Trust; Albert and Marie Diamant Bequest; Lady Northcote Trust Fund; The Margaret Sutherland Fund; Truby Williams Conservatorium Endowment. Special thanks also to Dr Harold Fabrikant for his wonderful commitment to orchestral training at the University of Melbourne.

Please contact Mr Peter Barron to discuss how you can support future Orchestral Tours or visit the University of Melbourne’s Believe campaign page.