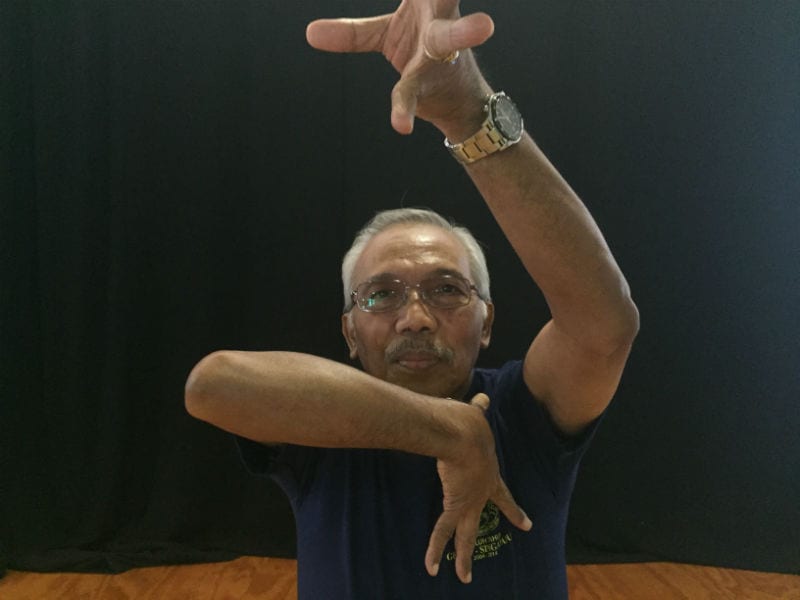

I Wayan Dibia: bringing Balinese traditions into performance study at the VCA

Professor I Wayan Dibia is a Senior Honorary Fellow in the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music and a master teacher from Bali. Each Summer, via the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music Global Atelier Program, students in the BFA (Acting) spend a week in Bali with Dibia, Senior Lecturer in Acting Budi Miller and local colleagues working on their craft, while learning about Balinese performance techniques. Dibia then comes to VCA and works with students from across the BFA (Acting) and BFA (Theatre) degrees, teaching the Balinese Hindu dance and music drama technique, Kecak. This innovative addition to the undergraduate program has a lasting impact on the students throughout their studies.

By Stephanie Juleff

Thanks for taking the time to chat between your workshops, Dibia. For someone who may have never heard of Kecak, can you tell us what it is and its origins?

Kecak is a Balinese tradition from the 1930s. It is a form that developed from a traditional trance dance called “Sanghyang” that involves mediums who, when they have entered a trance, are guided by villagers around the village to offer a blessing. To accompany that, they perform Kecak, a form of focal chanting.

It integrates multi-layers of rhythm of different rhythmic patterns composed of downbeats, upbeats and bridging. The most important element of Kecak, though, is the orchestration of voice, that sometimes imitates the melody of [traditional Balinese ensemble music style] Gamelan and the structure of Gamelan. So you hear some similarities of the Kecak voice in the structure of Gamelan because it’s all structured in even numbers like four, eight or 16. It’s all connected. Kecak is one of my specialities, that is why I love to share that with the students here.

You are here visiting the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music for the fourth time, and have an Honorary Professorship at the Faculty. How did that come about?

It’s a real honour to receive this kind of title here because for me the most important thing for me is to share the beauty of Balinese culture with Australian – especially VCA – students, because we are very close. We are actually neighbours, it’s only five hours away. So there’s no reason for me to not share the beauty of the arts because it will enrich the experience of theatre students or acting students in their creative works. We hope it will continue on for many years into the future.

Why do you think it’s important for students here in Australia to learn about and immerse themselves in Asian performance practices and make those connections?

Well, it is a cultural expression of the Balinese. But the form itself really provides the opportunity for the students here to learn how dance music and voice are integrated. As you know, in Western training sometimes, if you trained in dance, you only train in dance and movement.

In Kecak, it’s really giving you integration of all three elements. So with Kecak, one thing I would like to show is that with these integrations, different forms, of theatre and music and dance, are all integrated. They’re not separate. In introducing Kecak, I also introduce dance – classical Balinese dance. The idea is to give the students an experience into a new kind of movement that they may be able to utilise later on in their works. The idea is to enrich their experience and to see how they can use it as a new element in their works.

Tell me a little bit about the project you’re working on at the moment, a contemporary version of Antigone?

This story for me is a story of the past, but it’s talking about very contemporary situations because we still have the same problems now. There is power, a man in power who abuses that power and uses it to force injustice on people. How could two brothers, one is honoured as a hero while the other is left unburied.

For me, this is something that we have to remind our audience, that this kind of thing still happens, and to ask them, how can we respond? It’s a Greek story, but it’s still speaking about our world today.

Why do you think there’s been a resurgence in popularity in traditional performance practices in Bali?

In terms of the Balinese, well, because it is a part of their way of life. By doing this performance they are not only doing art, but also praying, participating in a temple ceremony. There is an obligation for you to participate in some way. So many people will perform dance or play Gamelans or something like that. For us in Bali, art is really part of our life.

Balinese culture and art right now does not only belong to the Balinese, it belongs to the world. It’s spread to different parts of the world. So it doesn’t strictly belong just to the Balinese and as it’s taken on by the local people, like for example in America or in Australia, they have the freedom to utilise whatever musical idea or dramatic ideas. So it’s a form that allows you to understand the cultural concepts of different culture. At the same time, you can input your own innovations based on your local culture. So Gamelan, dance and Kecak, it’s possible to do that with all three.

- Find out more about the Bachelor of Fine Arts (Theatre) and the Bachelor of Fine Arts (Acting).