Tillman Jex: life as an Interactive Composition grad in Berlin

Berlin was always part of the plan for Tillman Jex – and he knows how to make it work for him.

By Paul Dalgarno

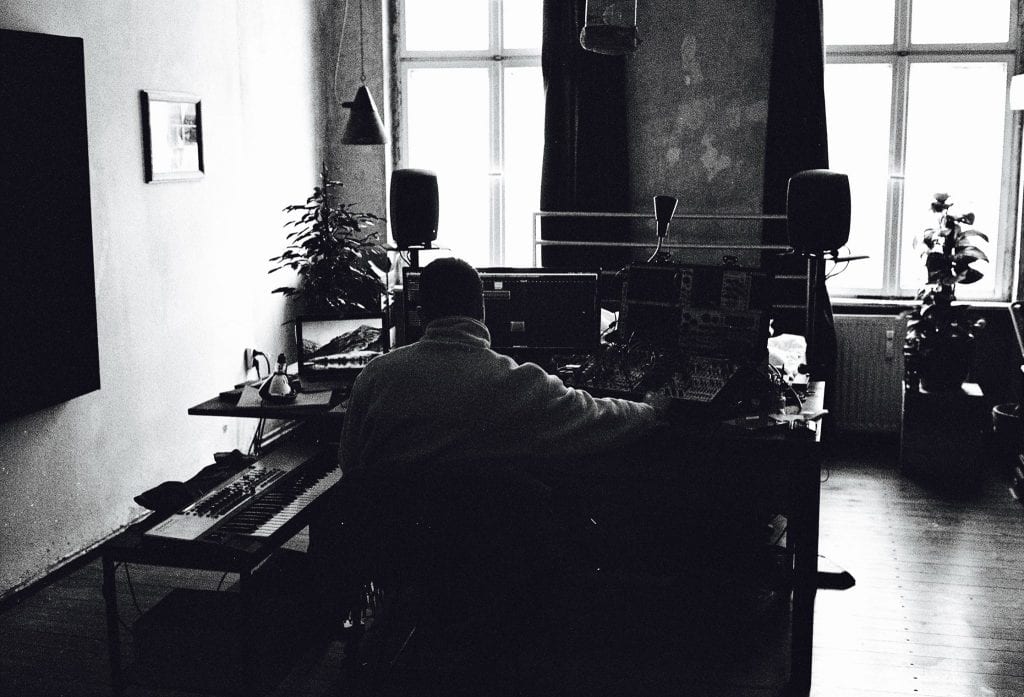

I have that sinking feeling as I sit with Tillman Jex in his bedroom-come-studio-come-living room in Friedrichshain, on the east bank of the River Spree in Berlin. Wires loop outwards from a module at the foot of his bed, into a desktop computer monitor and other bits of kit. His music – ambient, enticing – unveils itself slowly through the speakers. I nurse the tea he has made after boiling water on the stove. And still, I’m going down.

“Oh, yeah,” he says. “I should have warned you about that. The previous owners had rabbits running free in the apartment and they ate out the bottom of that chair.”

I sit forwards on the cushion’s edge, suddenly elevated, sip my tea.

Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990, Friedrichshain and neighbouring Kreuzberg quickly became home to punks and squatters, to artists and party-people from what for decades had been East and West. The timing of the that, and the sudden bonanza of abandoned warehouses, played into the birth of the club scene in Berlin which, nearly 30 years later, continues apace with Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg at its beating heart.

Jex – with one German parent, one Australian – had little doubt he would be moving to the city as soon as possible after graduating in Interactive Composition from the University of Melbourne at the end of 2016.

“I really wanted to soak up what was happening here,” he says. “To make music, basically, to see where that takes me while I have the chance.”

He arrived in the city mid-2017 and describes the experience so far as “really, really good”.

“I came over here with a particular style of music in mind that I’d been building towards at the end of uni. Sort of meditative techno, pulse-based rhythm music. Essentially, stuff you’d listen to in a club but with a focus on meditative, transcendental aspects.”

If that’s difficult to conceptualise, fear not: Jex recently published a 31-minute suite of music called Sub-Surface Oceans, which he’s been working on since 2016.

“It’s about nine planets,” he says, “although the current release only addresses six. Each planet represents a significant moment and they’re sort of characters and signposts in a bigger, overarching story.”

“Most people I send these big long tracks to don’t understand, which is fine. It’s music – you’re supposed to just listen and enjoy it at the end of the day, but they get confused by the form – it’s very long, and it changes and snakes around.”

We stand, examine the kit assembled on a table that, taken together, looks like the command station of some distant spaceship. There are cables, buttons, knobs, blinking lights …

“So, this is a modular synthesizer,” he says, pointing. “It’s a singular piece of music equipment made up of different individual modules, which have certain jobs. Kind of like what a puzzle piece is to a puzzle. The modules are manually connected to each other via physical patch cables and communicate that way, much like the old-school telephone patch cable system where you’d call the operator and they’d patch you into a friends telephone. It offers a lot of variability and flexibility.”

Close to that is an Access Virus TI synthesizer, which Jex says “was renowned in the early 2000s and sounds awesome. It’s for a desktop synth that’s played with a keyboard, like a standard synth.”

And in the middle there? That must be a mixing desk, right?

“Yeah, that’s the Soundcraft Signature 12 MTK,” he says, “which is an analog mixing desk. The inputs get converted to digital audio to run into the computer as separate channels. You can then record those or manipulate the sound.”

It’s the key bit of gear, he says, for the live set-up he’s working on. “The audio comes in from all my synthesizers and runs into my computer, where I process it in Max/MSP, a visual programming language. The signal comes back in on individual channels on the mixers, which is important because then I have live gain control, volume control, equalisation, and some extra effects if I want.”

Though techno remains a key interest, he was quickly disabused of the idea that Berlin’s techno scene would be “much more cerebral, more intelligent, and less momentary in the sense of people just partying and forgetting”.

“In reality, it’s not that different to the techno in Australia,” he says, sitting again. “But the party scene is a lot less controlled. I wouldn’t say there’s more drug-taking necessarily, but there’s more freedom with that aspect of things, and the culture, on the whole, is much more responsible.

“Most people are experimenting, opening their minds in a way – although, of course, that can have a really dark side as well.”

Tonight, as he does ten times a month, he’ll be tending reception in a hostel from 11pm to 7am. I screw up my face as his chair resumes eating me, try to look sympathetic.

“Everyone thinks it’s gross but it’s actually fine,” he says. “Lots of stuff is happening in Berlin at all hours so you don’t really feel detached or out of sync. Mostly I’m sitting behind a desk talking to drunk people or solving minor problems, but I can also watch Netflix or read or work on some musical ideas. It also gives you certain insights. There are 700 beds and I’d say about 50% of the guests at any one time have come to Berlin to party and experience the club scene.”

Mind music

That Jex should feel drawn to the the cerebral possibilities of music isn’t out of keeping with his other interests. Despite being a multi-instrumentalist (guitar, double bass, drums, piano, and guitar), with a father who is a drummer and composer, his plan on finishing high school in 2011 was to study psychology.

“I’m still really interested in psychology,” he says, “but the idea to actually go and study it and become a psychologist was born out of conceding to a cookie-cutter idea of educational progress, which is what I feel so many people get pushed into in high schools these days. That’s the business model – school and then university.”

In the event, he deferred his placement at Monash to take a gap year, following his mum’s advice to “do something useful” with his time by enrolling in a one-year sound production course at RMIT. “It was mostly about sound technology,” he says. “Mixing desks and signal paths and computer audio – that kind of thing. It ended up saving me from a lot of the leaning curve later on.”

On finishing at RMIT, he realised he wanted to apply for the Melbourne Conservatorium’s Interactive Composition degree, but was missing a portfolio of music, so took another year off in 2013. “In the first six months I actually did a massage therapy course,” he says. “That was another interest of mine, and another of my mum’s suggestions, and it gave me the money I needed to go travelling for three months.”

On his travels, he spent a month working on a farm in Umbria in central Italy – “where they had a piano, so I could also work on my portfolio” – before heading to Croatia, where he worked for Yacht Week (Official motto: Sail By Day And Party All Night Long).

“Yeah, it’s basically a party week,” he says. “You sail around the islands and party every single day and night.”

Sounds terrible, I say.

“Oh, yeah, it was,” he says, smiling. “And I spent a lot of my time working as a massage therapist while doing it, so that was even worse.”

He laughs, seems relaxed, sips his tea, a 25-year-old Melburnian in Berlin. “My music has really turned into this focus on trying to entice people to meditate and therefore enter into a detachment of the physical world,” he says.

Does he meditate? Did he meditate in the past?

“I did get really into it for a while,” he says, “but it’s dropped off massively since I came here. It’s really frustrating now – I can’t sit with my eyes closed for more than ten seconds without some random through corrupting me and taking me somewhere else.”

The form his meditation took, he says, was “the classic one of focussing on your breath and nothing else”.

“One time I actually floated out of my body and saw myself sitting there. When I realised what was happening I freaked out and was sucked back into my body. But while it lasted it was awesome. Learning how to train your attention in that way is super important for making music bit it also creates a lot of awareness about your own life. It becomes easier to breeze through everything.”

One of his grand plans at the moment is to work with others to create music for virtual reality projects. “The idea is basically to carry people though the whole meditative experience,” he says. “It’s artificial in a way, simulated meditation.”

Pockets of creativity

As part of his portfolio for the University of Melbourne, Jex attended a screening night at which Victorian College of the Arts Film and Television students pitched their film ideas and asked for help. He put up his hand to score a short film called ROT by VCA Film and Television Masters student Ruby Railey.

“I told her I really wanted to do it,” he says. “I asked if she could send me a cut of the film so I could put together a demo. In the back of my head I was like, ‘If she doesn’t use it I can maybe still use it in my portfolio’.

Railey used the music, the film won awards in New York, Toronto and LA, and the score formed part of Jex’s successful portfolio for an Interactive Composition degree at the University’s Southbank campus in 2014.

“I was always super excited to be there,” he says. “It was like our own little pocket of creativity because there were only art people studying on the campus. You could feel this melting pot of everyone swirling around and bumping into each other. There was always the potential for really awesome things to happen at some stage, for the two or three right people to meet each other and make something really cool.”

That potential, he says, is often overlooked by students. “It can be hard to break the ice and make the connections, particularly when you walk into the facilities of some other discipline. In my own case, there’s nothing I love more than to sit in the studio alone making music from dawn till dusk, but you have to also get out and meet people.

Shermaine Heng | 7 Deadly Sins | Grounded 2015 Melbourne. Music by Tillman Jex.

“That’s something that we can forget as young people who have grown up around computers. You feel you have access to the whole world. But the only way really, really good things happen is when people meet each other and put their minds to work, when they find a way through the good and bad ideas and get to know each other.”

It’s getting dark outside, Jex still seems relaxed, and it strikes me I could maybe go out partying with him, ask him to take me on a tour of the best clubs in the city. But then I remember he’s heading out to work at the hostel, his last shift before heading overseas for a seven-day music festival called Love International in Croatia.

Is he looking forward to it? Was there ever a more redundant question?

“Oh, yeah, it’s going to be great,” he says. “It’s right on the beach so you can dance, enjoy the music and dip into the water to recuperate whenever you want.”